At a committee meeting with affordable housing landlords on Wednesday, Council President Sara Nelson said she wanted to “examine” Seattle’s renter protections. The plain English translation of that politician-speak could mean reworks, rollbacks, or repeals to nominal working-class victories won by previous councils, such as the recent $10 cap on rental late fees, the First-in-Time ordinance, the 2019 roommate law, or the winter and school-year eviction moratoriums.

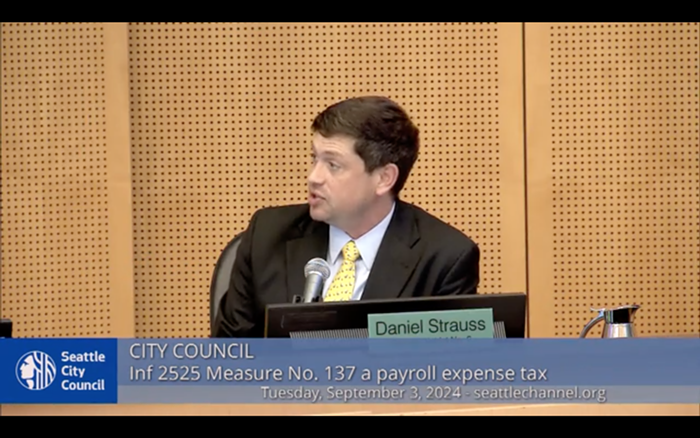

But Nelson, who prides herself on being a defender of landlords, seems to have ignored the actual content of the presentation from the affordable housing landlords. Rather than mentioning any of those city policies, the landlords lamented the slowness of the eviction process. That process will not speed up if Nelson gets to live out her post-argument shower fantasies and relitigate the last time renters’ rights champion and former City Council Kshama Sawant embarrassed her on the dais.

Attacking these modest protections under the guise of helping affordable housing landlords with concerns that seem more appropriate for state and county lawmakers would set up yet another stupid fight in Seattle, wherein the new council members would simply punish renters not to solve problems but rather to virtue-signal to their conservative base.

Investments Shmivestments

The affordable housing landlords who presented to the committee Wednesday played their hand very carefully.

“The nonprofits are really afraid of upsetting the progressive base,” developer Ben Maritz told The Stranger in a text. “They rely on that base to approve the housing levy that funds all of them. If the levy goes away, they all go away.”

During the public comment period, while landlords rattled off lists of the tenant protections they wanted to cut, Community Roots Housing Chief Operating Officer Andrew Oommen and Southeast Effective Development (SEED) Executive Director Michael Seiwerath focused mostly on increasing funding for their programs and clearing up the now infamous eviction backlog.

To avoid eviction, Oommen encouraged the council to consider funding more rental assistance, as they claimed to be seeing record nonpayment. He also suggested the council pay for some of the ongoing operating costs of affordable housing or resident services staff to help connect tenants to health and community resources. Seiwerath said the council could create a pipeline to put residents into permanent supportive housing, which would likely mean the City would have to pay to bolster that already limited supply.

But Nelson did not seem interested in the landlord's ideas that involved spending rather than evicting.

“We can't just keep talking about increased investments,” Nelson said. “…We need to examine some of our existing approaches and laws that are contributing to the problems that you are dealing with now, instead of just simply resorting to throwing more money at a problem.”

Nelson did not respond to my request for comment, if you can believe it. So, it is unclear which laws she would like to change.

Oommen and Seiwerath did not suggest cutting any protections in particular. In a follow-up email to The Stranger, Oommen said, “Unfortunately, it isn’t one law that slows down the process. It’s a collection of policies at the city, county, and state levels, and ever-changing case law, that’s causing the delays.”

He continued, “It’s also a resource issue. The need is in every direction–residents, housing providers, courts–all of us lack the resources to make our housing system work. This complex issue is going to take a comprehensive solution. That’s why we encourage the City Council to continue leading this public dialogue on how to balance the needs of our diverse communities.”

Other landlords at public comment named the $10 cap on rental late fees, the First-in-Time ordinance, the 2019 roommate law, and the winter and school-year eviction moratoriums as reasons they either have or will stop extracting wealth from tenants who live in their second, third, or 50th properties.

However it is unclear if the renter protections have actually driven owners away, and it's not like their homes drive off to Kirkland with them when they sell. A report from the City Auditor’s office last December found that the decline in properties owned by “mom and pop” landlords did not directly relate to new tenant laws between 2016 and 2022 but rather reflected a nationwide trend.

Just for the Fuck of It

Regardless, even if you accept the premise that the government should make it easier for landlords to make some tenants homeless, none of the local laws that Nelson has her eyes on would unclog the eviction backlog.

Reversing the $10 cap on late fees might give landlords some extra money, but it's unclear how much. Renters overwhelmingly pay their rent in full and on time, according to the Urban Institute, which studies rental payments to “mom and pop” landlords in particular. Tenants did so at similar rates before and after the city council passed the cap on late fees.

The First-in-Time ordinance, which went into effect in 2017, requires landlords to accept the first qualified applicant to provide a complete application in effort to combat discrimination. It also has nothing to do with eviction and seems most offensive to landlords based on the pure vibe of government overreach.

The 2019 roommate law limits a landlord's ability to screen roommates that tenants take on under existing leases. Landlords worry their residents will bring roommates who cause problems in the building. However, even if the City got rid of the roommate law, that wouldn't speed the process of evicting screened residents.

And, as I previously reported, the Housing Justice Project (HJP), which represents low-income tenants in court as part of the right-to-counsel law, does not use the school year and winter-eviction moratoriums very often.

“We can deal with whatever rules the City wants to put on us. We just need those rules to be clear, and enforceable in court,” Maritz said.

The Backlog

Right now, Maritz and other landlords argue the courts cannot enforce the laws due to the backlog. Many factors overwhelmed the courts—governments lifted COVID-19 moratoriums, nonprofits spent down their rental assistance funds, landlords filed more evictions than they did before the pandemic, landlords make simple errors in their paperwork, and now, under state law, every low-income renter gets a lawyer in eviction court, which can lengthen the process.

In the Wednesday presentation, Oommen argued the backlog is particularly problematic when dealing with violent tenants. He claimed that more residents of affordable housing buildings started using drugs and engaging in violent behavior in the past few years, and that it can take six to twelve months to evict them. In that time, a tenant’s violent behavior could push their neighbors to leave, or landlords may decide to keep units vacant so as to not put other residents in danger, he said.

Oommen did not provide any data to the council to indicate the scale of the problem, which Council Member Maritza Rivera called him out for. He did not respond to my questions about scope via email, either. According to HJP, only 47 of the 1,801 cases they completed intake information for since January 2024 involved a tenant with a behavior issue. That’s a little more than 2%.

Still, Seiwerath, while acknowledging the City's limited role, called on the city council to put “all [their] political will” toward working with the County to ensure “swift evictions" for those with violent behavior issues. Seiwerath did not respond to my request for a follow-up interview.

But there’s not much the City can do about the backlog, because the fix requires an amendment to the state constitution. Besides, the King County Superior Court already adopted an emergency rule last month to expedite the eviction process when landlords can show evidence that the tenant’s behavior “substantially” impacts the health and safety of other residents. However, HJP Managing Attorney Edmund Witter said that his team has not seen any landlords use the new rule to expedite a case. He speculated that is because most evictions related to behavior win by default. Maritz also said he has not used the new rule and doesn’t know anyone who has. He’s not sure if the court has published instructions on how to use the expedited path. King County Superior Court did not respond to my request for comment.

Not to give landlords any ideas—trust me, they already have them, and they are not making it 1,200 words into a story by The Stranger—but the council could show their unwavering solidarity with the landed gentry by attacking the right to counsel.

The landlord presenters did not call for an end to right-to-counsel, but they didn’t praise it, either. Oomen called the right a “very interesting innovation.” The Seattle City Council passed the right for low-income renters in March 2021. The new council could not meaningfully repeal their law because Washington state passed it later that same year.

However, the council could kneecap the right by defunding HJP, which the City, County, and State pay to represent low-income renters in eviction court. Most of their budget comes from the State, a $5.2 million contract, but the City of Seattle funded HJP a little more than $1 million for 2024.

If in the upcoming budget negotiations the council defunded HJP, the organization would have fewer attorneys to take appointments. Witter said that HJP could ask for continuances when they don’t have an attorney available, but he agrees that if the City tries to undermine the right to counsel, “every landlord would be able to take advantage of a tenant’s lack of legal resources and likely inability to navigate the court system … so [landlords] would likely get more uncontested evictions just because the tenant doesn’t show up and doesn't have anyone to help.”

While all these fights brew in the background, Housing & Human Services Chair Cathy Moore has not made clear what her next course of action will be. She did not respond to requests for comment.

But if Moore comes for tenants’ rights, she’ll draw lefty wrath yet again.