Sex worker advocacy groups plan to oppose legislation from Seattle City Council Member Cathy Moore that would make prostitution loitering a misdemeanor crime in Seattle. Moore claims the bill would help people escape the sex trade and decrease gun violence that endangers Aurora businesses and homeowners, but advocates say this bill only endangers sex workers and disproportionately targets women of color and members of the LGBTQ+ for arrest, all without increasing needed services.

Moore’s bill would reinstate a Seattle law that made “prostitution loitering” a misdemeanor, which the city council unanimously repealed in 2020. Violators would face up to 90 days in jail and a fine of $1,000.

Under the law, cops could arrest people for hanging around and beckoning passersby, or walking up to a car and leaning through the window to talk to the driver in a way that gives off sex worker vibes.

The bill also creates a promoting prostitution loitering gross misdemeanor crime. Violators of that law would face up to a year in jail and a $5,000 fine.

Finally, the legislation creates a seven-mile Stay Out of Area Prostitution zone (SOAP) that stretches along Aurora Avenue from 85th Street North to 145th Street North. Judges can impose a SOAP order as part of pre-trial or sentencing conditions on people arrested for or convicted of any prostitution-related crime, and cops can arrest people caught violating the SOAP order on a gross misdemeanor.

The groups opposing the legislation include Strippers Are Workers (SAW), a dancer-led advocacy group that recently won a major victory in Olympia to reintroduce alcohol into strip clubs. SAW Campaign Manager Madison Zack-Wu said that when the council repealed the City’s loitering law in 2020, they acknowledged the law as “racist, transphobic, and classist” and that it mostly hurt sex workers and victims of trafficking while doing nothing to actually prevent crime.

Zack-Wu expects about a dozen sex worker and LGBTQ+ organizations to sign onto a letter later this week urging the Council, Republican City Attorney Ann Davison, and Mayor Bruce Harrell to drop the prostitution loitering bill. Already, a separate letter writing campaign organized by SAW spurred people to send in thousands of letters to city council members and to Harrell declaring their opposition to the bill.

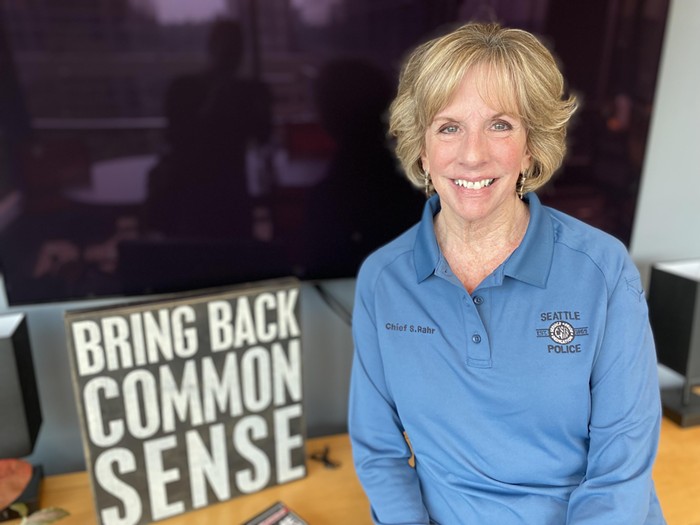

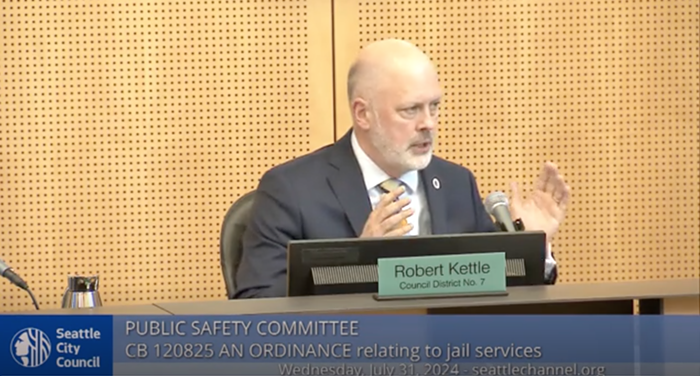

At a press conference last Thursday, where Moore announced her bill alongside Davison and Council Member Bob Kettle, Moore justified the legislation as a way to intervene in sex workers’ relationships with their pimps, or traffickers. She argued that police officers needed a way to remove workers from possible exploitative situations, and she apparently prefers this way, which forces sex workers to engage with police under threat of criminal sanctions. She promised diversion programs for the people arrested on prostitution charges, as well as funding for a possible emergency shelter, plus money to help people remove prostitution arrests from their record. Moore also argued that by targeting sex workers, the police could reduce gun violence in the area.

A torrent of arguments against Moore’s policy has rushed in from all sides. In a phone interview with The Stranger, former Democratic Seattle City Attorney Pete Holmes came in hot and said that sending cops to intervene in these workers’ lives actually puts them at risk for more sexual abuse, not least of all from cops themselves. On multiple occasions, law enforcement agencies caught Seattle Police Department (SPD) officers trying to pay for sexual encounters, including Officer Daniel Espinoza, who remains employed by SPD. In 2023, the City paid a woman nearly $2 million to settle her lawsuit after she claimed an SPD officer and his partner forcibly raped her when she worked as an underage sex worker. Considering this council’s lack of interest in holding cops accountable, adding the prostitution loitering law would be like giving cops a “hunting license” for sex workers, Holmes said.

Of course, the legislation and Moore’s rhetoric implicitly forecloses on the idea that sex workers can consent to sex work or possess any agency at all. Rather than seek to re-criminalize consensual sex work, Holmes said the legal system should focus its resources on cases of abuse. “If a sex seller calls to say that she was assaulted by a sex buyer,” that’s when the legal system should respond, he said.

Though Moore also justified the bill as a way to cut down on gun violence associated with the sex trade, the Greenlight Project, a peer-led mutual aid group that serves sex workers on Aurora, said the legislation does nothing to address it. Spokesperson Amber argued that sex workers aren’t committing violent crimes, and that they–like nearby business owners–also do not want to get caught in shoot-outs. And yet, the brunt of this bill’s enforcement falls on arresting sex workers and “promoters,” which can include people just dropping off a friend to work at Aurora. These laws help to isolate sex workers, making them more vulnerable, Amber said. When this law existed before, she added, fewer workers walked in groups, reducing security even further.

If SPD officers decide only to arrest these workers, they still face jail time or possible prosecution, which can trap them in dire straits. While Davison promised diversion, realistically, any pimps or traffickers who actually do control workers will prevent them from participating in those sorts of programs, according to Audrey Baedke, the cofounder and director of training and partnerships at Real Escape from the Sex Trade (REST).

REST provides services to transgender and cis-women trying to escape the sex trade, and they’re the only organization providing wraparound services and extended housing for this population group. Women can stay for up to 90 days, and the program aims to help them exit into stable housing. The problem is that REST only has seven beds, and they’re almost constantly at 90% capacity. The organization often diverts people it cannot help to domestic violence shelters, but those shelters also struggle with capacity.

Baedke said REST took no official stance on the prostitution loitering law, though they appreciated the council’s attempt to use cops to go after the sex buyers and sex sellers. The organization also acknowledged that people working in the sex trade can find interactions with law enforcement confusing, and they pointed out that police can be customers.

Sex workers who leave the trade have told REST that the most helpful thing law enforcement can do when interacting with workers is to provide real services, but at the moment Seattle and King County have very little to offer. Baedke stressed that REST doesn’t have the capacity to help all the people calling its hotline, and without more money it cannot handle the increase in demand resulting from this bill.

In Thursday’s press conference, Davison did not detail out what happens if workers refuse to participate in a diversion program, but the law leaves open the possibility that these arrests could lead to a conviction.

A prostitution arrest on a person’s record can make it harder for them to secure housing or find a job, and the imposition of court fines and fees can make leaving sex work that much harder, said Elizabeth Hendren, advocacy counsel at the Sexual Violence Law Center (SVLC), one of the groups signed on to oppose Moore’s bill. The SVLC provides trauma-informed legal counsel to victims of sexual and gender-based violence, including former sex workers. While Moore’s legislation may offer some funding to help remove charges from a person’s record, that process can take years and requires at least one–and maybe more–full-time attorneys, Hendren said. The easiest way to prevent people from suffering under the weight of a prostitution charge is not to not put a charge on their record in the first place, she argued.

In an email, even former City Council Member Alex Pedersen, one of the previous council’s more conservative members, suggested Moore should consider removing the portion of the bill that criminalizes workers. Pedersen co-sponsored the original prostitution loitering law repeal in June 2020, along with Council Members Andrew Lewis and Tammy Morales. After reading Moore’s bill, Pedersen said he appreciated the parts that targeted pimps and johns for arrest. He also had no problem with the plan for a SOAP on seven miles of Aurora Avenue. However, he argued the bill included a “problematic portion” in its targeting of workers, and he said it possibly “encroached” on a person’s right to free speech and free assembly.

Amy-Marie Merrell, executive director of the Cupcake Girls, an anti-trafficking organization that works with people who want to leave or remain in the sex trade, said their organization never forces workers down any particular path because they’ve “already dealt with enough coercion.” Cupcake Girls also signed on to oppose Moore’s bill because her plan targets the most at-risk population of sex workers–that is, people out on the streets–and offers them nothing but bad options, Merrell said. If Moore really wanted to help these women, Merrell added, then she’d offer them housing, a basic income, or some kind of real, sustainable option for exiting the sex trade. In offering none of the help these workers actually need, the bill may only push some people off Aurora and into deeper, darker, far riskier shadows.