On Tuesday, after more than three hours of overwhelmingly negative comments about the Seattle City Council’s proposed Stay Out of Drug Area (SODA) zones, its Stay Out of Area Prostitution (SOAP) zone, and the reinstatement of the City’s prostitution loitering laws, the council voted 8 to 1 to pass all that stuff. Members of the public, residents of these zones, sex workers, and major organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington, the MLK Labor Union, and Purpose Dignity Action opposed the bills. But, as with the gig worker minimum wage repeal attempt earlier this year, the council seemed uninterested in meaningfully engaging with major organizations and those with lived experience who did not happen to belong to the orgs telling them what they want to hear.

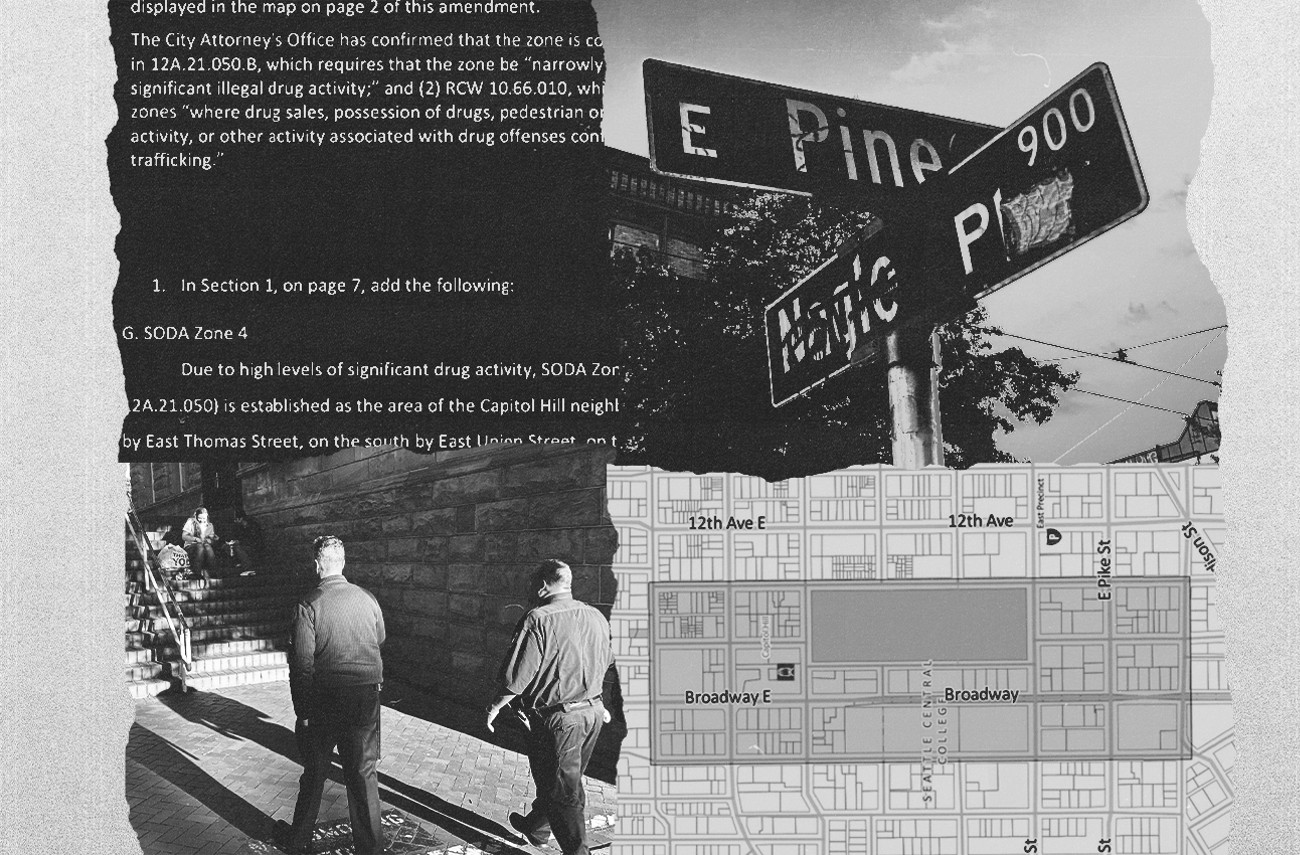

The bills the council passed Tuesday would allow judges to ban people from certain parts of town if they’re caught in that area possessing or selling drugs or committing a list of other crimes with a connection to drugs. That list includes assault, harassment, theft, criminal trespass, property destruction, and unlawful use or possession of weapons. That means a cop could arrest someone for stealing grapes from the QFC on Pike Street, catch that person with drugs on them, and then a judge could banish that person from Capitol Hill. The council placed the zones throughout the City, including along a stretch of Broadway on Capitol Hill, along University Avenue, in Belltown, downtown, and in the Chinatown-International District. They created a similar banishment policy for crimes related to prostitution, establishing the SOAP zone along a seven-mile stretch of Aurora.

It’s Giving “Police State”

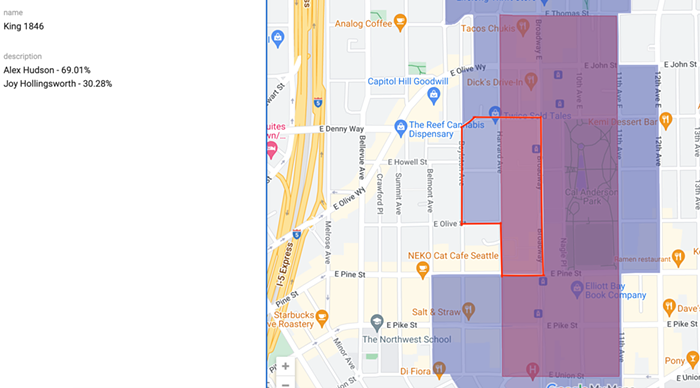

Aside from the big turnout at City Hall to oppose these bills, precinct data casts doubt on whether most voters who live in these areas support these policies. In half the zones, voters cast ballots against the current city council members in the 2023 election. Exceptions included the downtown and Pioneer Square. (See full map overlay here.)

In Belltown, former Council Member Andrew Lewis won every single precinct in Public Safety Committee Chair Bob Kettle’s proposed SODA zone, which starts at Battery Street and 4th Avenue, running down 4th to Blanchard, then east to 2nd Avenue, before looping north back up to Battery. Lewis and Kettle had a tight race in a couple of the precincts, but Lewis won at least one by more than 70%.

In the University District, Council Member Maritza Rivera’s SODA zone starts with a northern boundary at 52nd Street and runs south along 15th Avenue all the way to 43rd Street before heading back up north along Brooklyn Avenue. Rivera won zero precincts in that area. Her opponent, Ron Davis, captured most of the precincts in and around the SODA zone by more than 60 percent, and in at least two precincts he won by more than 70 percent, according to the Washington Community Alliance General Election map.

The Chinatown-International District (CID) SODA zone proposed by Council Member Tanya Woo, which draws a northern border on South Main Street, runs south along Boren Avenue and Rainier Avenue South until it hits Dearborn Street, and then heads west to 7th Avenue South, the western edge of Interstate 5. The zone also loops in all off-ramps and areas underneath the interstates and adjacent sidewalks. Only a small portion of the western-most part of the CID zone includes a precinct that voted for Woo. The largest section of the zone covered a precinct of which 55 percent voted for Council Member Tammy Morales. On Monday, the International Examiner published an open letter from the Chinatown International District Coalition, who said they were “disappointed with Councilmember Tanya Woo’s actions to further criminalize our community and wish to make it known that Woo does not speak for the neighborhood.”

In District 3, which encompasses Capitol Hill, Council Member Joy Hollingsworth won zero precincts in the SODA zone she created, which starts on Thomas Street, runs south along 11th Avenue to Union Street, then heads back north along Harvard Avenue until it reaches Thomas again, and covers most of Capitol Hill’s Broadway Avenue core and Cal Anderson Park. Alex Hudson won almost every single precinct in that SODA zone with more than 60 percent of the vote, except for one precinct she won by 59 percent.

Multiple residents who said they lived in Hollingsworth’s district showed up to the public comment period Tuesday to voice their opposition to the SODA and SOAP zones, including a homeowner, a licensed social worker, the sister of a sex worker, a union representative, and a mutual aid organizer. Most of the commenters complained about how the bills would be ineffective, would prevent people from accessing services, and would waste public funds on a failed policy. One woman said, “Banishment is not diversion, banishment is not care, and banishment does not work.”

The Seattle LGBTQ+ Commission also came out against the establishment of SODA and SOAP zones. LGBTQ+ Commissioner Andrew Ashiofu said he lives in the SODA zone and walks up and down Broadway Avenue everyday. He said Capitol Hill residents want and need more harm reduction, more funding for services, and more humane policies, not more policing.

The day before the council voted on the zones, I knocked on doors in Capitol Hill and waylaid people walking around in the SOAP zone to gather their opinions on the legislation. Kyle Pace, who lives in the SODA zone on Harvard Avenue, says he knows his street sometimes lands on the top 10 places in Seattle with the most crime and overdoses, but he doubted that the SODA zone can address that issue. He thinks the zone will just move the crime somewhere else, and he doubted it would make him safer. He also confirmed he did not vote for Hollingsworth. I interviewed about eight people who all shared the concern that the SODA zones just pushed people around. Some agreed that they wanted to see Capitol Hill become safer, but not at the expense of other neighborhoods. Two women sitting in Cal Anderson Park say that the laws “were giving police state.”

Even supporters of the Capitol Hill SODA zone recognized that the policy fails to actually solve any issues regarding drug use, homelessness, and crime, and they understand it just pushes people around. At the first public hearing regarding the legislation, the Capitol Hill Business Association (CHBA) complained that a downtown SODA zone might push people up to Capitol Hill to buy drugs and do crimes, and said they’d oppose the bill, says CHBA Policy Counsel Gabriel Neuman. But after Council Member Hollingsworth’s office contacted them about a potential zone on Capitol Hill, CHBA reversed its position and said they wanted the zone implemented.

Neuman says the CHBA wants cops to come when called and, for instance, sweep homeless people who set up their tents on the patios of neighborhood restaurants. Though businesses, he argued, would prefer a police alternative to handle the task of sweeping away homeless people and banishing them from returning. Those alternatives don’t exist right now, and they never will if the City maintains its memorandum of understanding with the Seattle Police Officers Guild.

“Poorly constructed, largely impossible to enforce”

Residents are right to express skepticism about these laws. The City tried similar strategies in the past, including in 2015 when Seattle Mayor Ed Murray tried a “9 1/2 block strategy,” where the City increased police presence and arrests in the downtown core. The Murray administration took a victory lap at one point after crime numbers dropped in the targeted zone. However, the Seattle Times found that crime increased in all the surrounding neighborhoods.

Council Member Tammy Morales, the sole person to vote against exclusion zones and the resurrection of the prostitution loitering law, opposed the bill for three reasons, she said at the meeting. First, she argued, they’re simply rehashed, failed policies. Second, the council majority’s aim to “disrupt” drug markets will increase overdose deaths because people will turn to more unreliable dealers, Morales said, citing a study from Indianapolis that looked at the effect of law enforcement disruptions of drug markets on crime and overdose deaths. The study also found disruption of drug markets often led to increases in violent crime in the area. And while the council claims the SODA zones target drug dealers, Morales emphasized that the law does not apply to King County judges, who handle felony cases such as drug dealing and drug trafficking. The law primarily targets low-level drug users, not drug dealers.

Finally, Morales pointed out that many of these zones actually include places where people receive services. The Stranger and DivestSPD overlaid the SODA and SOAP zones on a map of service providers listed in the Emerald City Resource Guide, which is produced by Real Change. The zones include locations such as the King County Public Defender’s Office, one of the REACH locations (a homelessness outreach organization), and Planned Parenthood, as well as some food banks, reentry programs, and treatment providers.

The laws provide exceptions for people under a court exclusion order if they have an appointment with a medical or service provider, but, during her testimony before the council at its last committee hearing on this bill, King County Department of Public Defense Director Anita Khandelwal said that many public defense clients don’t have phones or stable housing, and many just drop in to talk to their attorneys. She said the Pioneer Square SODA zone could interfere with her public defenders’ ability to represent their clients.

During the hearing, as Council Member Kettle justified the use of the SODA zones, he paid lip service to the claim that he wants to lead with compassion and make sure people can access the help and services they need. However, in an interview Tuesday with The Stranger, Alison Eisinger, executive director of the Seattle/King County Coalition on Homelessness, says the council passed this bill in such a way as to make it almost impossible for service providers to give meaningful input on the policy. Eisinger argued that because the council mostly ignored suggestions from knowledgeable partners on this policy, the law will likely be largely ineffective and difficult to implement. Even if the Seattle Police Department finds the law difficult to enforce, she still expects it to do real harm by interrupting services, sending more unhoused people and people of color to jail, and ultimately undermining the effective outreach strategies that the people of Seattle already pay for.