I stood against the red walls of the warehouse-turned-gym. Fake cobwebs covered exercise equipment pushed up against the sides of the room to accommodate a whooping, hollering audience seated in folding chairs. Attendees wore their coats indoors to protect against the morning chill in the drafty, uninsulated room. A pit crew of spotters and helpers adjusted the heights of the racks on two platforms at the front of the room, then they loaded on round plates of weight.

I was going to do this. I was going to squat. First, 110 pounds. Then, presumably, more. I had three attempts to squat as much weight as I could while following the judge’s commands: squat when she says down, wait to unload the burden until she says rack. Got it.

After the squat, I would bench press. After the bench press, I would deadlift, or pull a bar laden with weight up half of my body and then set it back down. I would do all of this dressed as a witch. Except, in the chaos of the morning, I’d lost my hat. I looked more like a pirate without it. But as I eyed the rack, a lost hat was the least of my worries.

I never thought of myself as a strong person. I dreaded moving homes because lifting furniture up twisting staircases made me reckon with the limits of my own body. I avoided the free weight areas of the gym. Weights were a foreign language. I preferred to stick to my native tongue—treadmills and ellipticals.

My thinking changed four weeks ago, when I started training with Leanna Carr, 32, a nonbinary, seasoned powerlifter and co-owner of Rain City Fit’s Barbell Club. Powerlifting is the subset of weightlifting focused on forming “absolute strength” in the squat, bench, and deadlift. Historically, men have dominated the sport. At RCF, Carr helped facilitate a community of women, queer, and nonbinary powerlifters.

For my latest exploration into Seattle’s subcultures, I immersed myself in this powerlifting community with Carr as my guide, and I became a powerlifter myself.

Before the calluses had even formed on my palms, I agreed to compete in a Halloween-themed powerlifting meet in Portland. Through this process I found a supportive community, a weird gym, and strength in myself, both physical and mental.

It's Not for the Girls

In my experience as a woman with a body, I've noticed that people have a lot of opinions about how it should look. Those opinions shape how we shape, or think about shaping, our bodies. Somehow, I've moved through life without anyone telling me to lift weights, which is weird, because women stand to benefit more than men from resistance training. Weight lifting can stave off osteoporosis by building up bone density, and women are actually physiologically more capable than men at lifting more weight for longer periods of time.

And yet: “Go to your local gym and you’ll see the demographic of people lifting is men,” Carr said.

Blame society.

When Carr first started powerlifting, they remember their mom worrying they would “look like the Hulk.”

“There was a huge stigma when I started lifting,” Carr said. “Being Asian, telling my mom I’m getting big and strong, she made comments like, ‘Don’t get too big.’”

At the time, Carr identified as a woman and presented as more feminine. Stereotypes for Asian women promote delicate, slender bodies. “You’re not supposed to get bigger, you’re not supposed to take up space,” Carr said. “Society is very anti- women getting more masculine or building more muscle.”

Carr spent their early life in Georgia as a competitive cheerleader. When an injury sidelined them from the sport, they took up bodybuilding, weightlifting’s heavily spray-tanned, physique-focused cousin. They worked out to lose weight, and they lifted only to carve vanity muscles. In the process, they developed an eating disorder and body dysmorphia.

Picking up powerlifting flipped a switch in Carr. They stopped watching the scale. The only weight they cared about was how much they could load on the bar. Food became fuel, a necessity if they wanted to reach any of their lifting goals. Through powerlifting, Carr gained a sense of self they lacked as a closeted queer person in the South.

“It felt really cool to take up space for the first time in my life,” Carr said. They wore baggy sweatpants. A layer of hot pink cut into their dark hair. Tattoos swirled around their arms, their neck. “A lot of the confidence I got during that time period translated to my everyday life and figuring out who I was," they said.

Other women, gender-nonconforming, and queer people who power lift at RCF have seen similarly positive impacts to their life because of the sport.

The Body

The first day I went to the Barbell Club to lift with Carr, women and queer people outnumbered the men in the gym.

Carr walked me through warm-ups for squats—lunges, resistance-banded side-steps, body weight squats—and introduced me to the squat bar. The bodyweight squats alone were hard. Meanwhile, Claire Zai, 28, huffed through a 300-pound squat on the platform behind me.

Zai, a powerlifting coach heading to medical school to become a gynecologist, loves “the transformative nature of being able to come into the gym and build my own body into something I love.” I swear her quads could crush a grown man’s skull.

It’s similar for Sasha Naomi, 24. Naomi is trans and started powerlifting more than a year ago.

“There’s a lot that’s really powerful about changing your body and taking control of it in the way I choose,” Naomi said.

As someone who has transitioned genders, Naomi values the ability powerlifting gives her to “take back pieces of my body from my old self.”

Even more than the physical benefits of powerlifting, Naomi likes how capable it makes her feel. She especially likes the deadlift. “It’s not so much about being able to do something that I thought I couldn't do, it’s about knowing that I could do it all along,” she said.

I talked to a trans dancer named Kit from the Triple Door who recently started lifting their fellow dancers after starting to power lift. The strength gained from weight training felt affirming for her.

“The ability to believe in myself and my ability to trust the process and trust that things are going to be okay comes from powerlifting,” Zai said. She currently maxes out on the squat at 425 pounds.

Carr loaded weights on the squat bar to see how much I could squat. By the end of the session, my quads burning, I was up to 95 pounds.

Afterward, I tested out a bodyweight squat. My body practically floated; it felt so light and easy. My mood, too, improved. I chattered with Carr, bubbling.

"Weightlifting can help folks find more confidence in themselves just by being able to lift weights they never thought were possible,” Carr said.

Two weeks into my training, I roasted a whole chicken for the first time. I attribute my confidence in attempting the task to powerlifting.

The Mind

Soon, I learned to deadlift. In front of a wall of cat posters in the main RCF gym, I hinged my hips and lowered my body, grabbed the weight, and pulled it up to my hips, scraping it against my shins. After I let it down, energy surged through me. What the fuck? I didn’t know I could do that. In our first deadlift session, I lifted 130 pounds.

Things didn't always go smoothly, though. My bench press progress felt incremental, barely budging from 55 pounds to 65 pounds during training. With squats, I thought I had things down pat. Yet, in our second session, the exercise didn’t go so seamlessly. My legs cramped, the weight felt heavier. With only a fraction of what I had done the last time on the bar, I squatted and couldn’t get back up.

Carr, spotting behind me, swooped in and pulled the bar off of me. Still, it shook me. I was both embarrassed by my failure and rattled by the feeling of the weight pressing down on me.

“You can totally lift that weight,” Carr said. “It’s all mental.”

Carr explained what happened: My form slipped, I tried to recorrect, and it threw me off.

“You bombed out,” Carr said. “Don’t worry, it happens to everyone.”

Logically, I knew I was bound to fail at some point. Failure drives powerlifting, a sport that demands its participants not only test their limits but run headfirst into them. As someone who keeps tying up personal performance with self-worth, I wanted to avoid the failure aspect for as long as possible.

“You just gotta shake it off and get past it,” Carr said.

After some rest, with them in my ear hyping me up, I nailed the lift.

This community support happens all the time in powerlifting, and especially at RCF.

The Spirit

RCF is warm and eclectic. The main gym space in the heart of the Pike/Pine corridor on Capitol Hill stretches into a big warehouse once used for food storage for an Italian restaurant. Upstairs, in what used to be offices, RCF gobbled up all the available space it could. The result is a maze of rooms. Some rooms feature a host of house plants sunning themselves under slanted skylights next to the bench presses, others have ropes of string lights slung in the rafters high above the workout equipment. There are no mirrors. A giant, stuffed bear sits at a piano next to a deadlift area. Pride flags from every identity cover the walls.

Its community is as warm and welcoming as all of RCF’s locations. RCF prides itself on being a safe, inclusive space.

“This space is intentional for these more marginalized groups of people,” Carr said. “Those are the people we are going to encourage to take up space. If that’s not what you’re about, then go to 24-Hour Fitness.”

The gym community transcends the weight room. RCF members have a book club (in September they discussed Kathryn Harlan’s book of short stories, Fruiting Bodies), they have a Dungeons & Dragons group, a gear-swap group, and a group all about mental health resources.

“We've cultivated something even I’m in awe of all the time,” Carr said. “Our community has empathy. They care.”

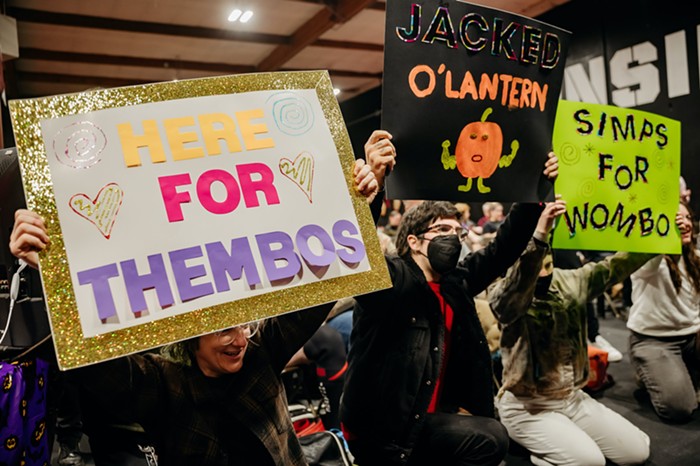

Carr plans meet-ups, including multiple days where the Barbell Club is reserved for “theys and femmes” to lift. During one of those events in October, I deadlifted while The Chicks’ “Cowboy Take Me Away” played, Zai gave me feedback on my form, and a slew of women stretched on a mat while talking about their cats. I wish working out felt like that all the time.

Carr also plans three to four powerlifting competitions each year under Rain City Powerlifting Union (RCPU), the powerlifting federation RCF created to make space for genderqueer and trans people to participate in the sport. RCPU has a nonbinary category for lifters. The meets try to counter to the toxic masculine intensity present in regular powerlifting meets.

“We see powerlifting as something that should be fun and should be for everybody,” Carr said. “People who lift should be able to lift exactly as they are and be affirmed in who they are.”

Early into my powerlifting journey, I said fuck it and joined them for one of these meets.

Competition

Lifters dressed as caterpillars, Chucky dolls, UPS delivery men, Kim Possible, sexy buff nuns, and so on, filled the gym. The room smelled faintly of rubber and sweat. Music thumped. This was RCPU's "Nightmare in Stumptown" event. Four weeks into powerlifting, here I was at an out-of-state powerlifting competition. Life is weird.

For the competition, I had three attempts at each lift (bench, squat, deadlift). After nailing one, the next would increase in weight. By the third attempt, I should be lifting the most I could, maybe even more than I could.

I was so nervous I could barely swallow down the fried egg sandwich I ate for breakfast. My worst fear was failing another squat. Especially in front of a whole audience.

After a frantic morning of warming up, meeting a new RCF coach to help me during the day since Carr was emceeing, it was my turn. Carr, while making the introductory announcements dressed in hot pink '80s workout garb, locked eyes with me. They grinned encouragingly.

"Platform one, the bar is ready," Carr announced. They called my name.

Once the bar was on my shoulders, everything passed in a blur. The judge said, "Down," and I lowered myself to my heels, shot up, waited for the "rack" command, and unburdened myself. My face broke into a smile. The whole room cheered.

The next lifters took the platform. Their starting weights doubled mine. I tried not to worry—I just started doing this, I reminded myself. Plus, the only person I was really competing with was myself. I gaped watching other lifters attempt weights they'd never lifted before in front of an audience. Their faces turned purple with effort, their bodies shook, and—they couldn't do it. The spotters swooped in. The crowd cheered loudest during these times. Failure has a different definition here. I'm still trying to parse it.

I ended up lifting more weight than I ever had in training with the squat (132 pounds) and deadlift (176 pounds). The benchpress was another, less impressive 72-pound story. Whatever.

After my final lift, completely depleted, light-headed, and buzzing with the accomplishment, I ran over to Carr, who was still emceeing, and hugged them. For a month, they'd given me support, guidance, and a skill that's made me carry my head higher. I like seeing proof of my own deltoids. I also like knowing a little bit more about what I'm capable of. I can lift the equivalent of a small horse and flawlessly roast a chicken.

You can too.