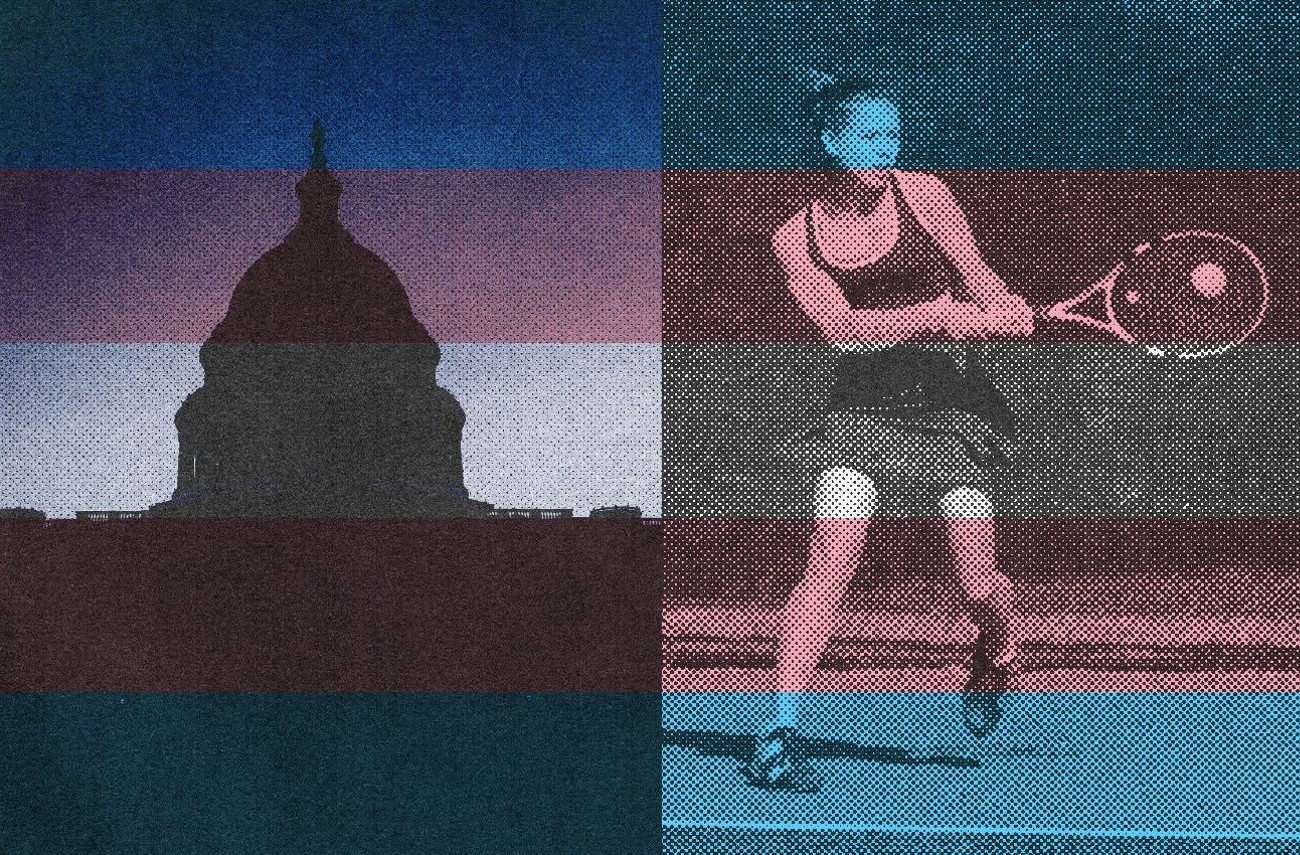

In April, the Biden Administration finalized revisions to Title IX regulations, the federal policy protecting students from sex-based discrimination.

The changes should take effect on August 1, and there’s a lot to like about them. The Biden Administration undid Trump-era policies dictating the way K-12 schools, colleges, and universities should respond to sexual crimes, and it also clarified that Title IX protected gay and trans kids from discrimination. Despite the legal gains for queer students, however, trans athletes were not mentioned.

When the administration proposed blocking all-out bans on trans athletes last year, it kind of seemed as if Joe Biden would set a stake in the ground for trans athletes. But, according to sources “familiar with administration planning” who spoke to the Washington Post, such protections are unlikely to materialize before the presidential election.

So, where does that leave trans athletes? US Supreme and Circuit Court decisions have found that Title IX protects trans people–and trans athletes specifically in one recent case from West Virginia–but it's still an unsettled area of law that allows for restrictions in 25 states. And six Republican Attorneys General, convinced that Biden’s changes to Title IX do allow transgender athletes to compete, have sued to maintain their discriminatory status quos. The courts will keep on courting and sort it out in time (maybe).

Even in Washington’s bluer pastures, state law does not explicitly address athletic participation, but LGBTQ legal advocates who spoke to The Stranger said a progressive K-12 policy and a state anti-discrimination statute protect them.

In 2008, the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association (WIAA), the nonprofit rule-making body for K-12 athletics in Washington, enacted the first sports policy for trans students of its kind. It allowed students at every grade level to play on the teams that aligned with their gender identity after their school’s Athletic Director had deemed them eligible for play. No surgery, no hormones, and no proof were needed.

Aidan Key helped write the WIAA policy in 2008. The founder of the Seattle nonprofit Gender Diversity was one of four transgender people called in to help the WIAA fix the policy it had developed the previous year. Advocates had pointed out that the WIAA’s blend of criteria from the NCAA and Olympic Committee made no sense for children because they mandated things like surgical intervention.

As lawyers from the National Center for Lesbian Rights and ACLU vigorously debated an alternative solution based on body mass index, Key raised his hand and waited for the moderator to call on him. He asserted that self-identification needed to be the baseline, and that a review committee could address any exceptional situations as they arose. In 10 years, only one case came up for review. Key said the girl’s teammates wrote a letter of support that encouraged her to change with them in the locker room instead of the bathroom she’d been cloistering herself in. The WIAA later struck the review process, meaning if a school determines a student is eligible for sports–boom–end of story.

Key said in the last 15 years, he’s helped the WIAA update the policy to address nonbinary students, a term that wasn’t common-use in 2008; in 2021, Gender Diversity and the WIAA developed a gold standard document for trans athletics called The Gender Diverse Youth Sport Inclusivity Toolkit. The resource guide is meant to educate administrators, coaches, and parents on local policies, federal law, terminology, and the state’s history with inclusive sports practices. Kay said their influential toolkit has circulated the country, landing in the hands of athletic directors in places like Los Angeles and Chicago.

Key said he understands why people have questions about trans athletes when we’re so used to dividing sports by gender and for reasons of equity: “It’s just, to me, a continuation of that work.”

“The threat [of trans student athletes] is nonexistent,” Key added. “Their stats, their scores, and their times for the various competitions and team sports are right there with their peers. I’m up for keeping an eye on things and reflecting on what we’ve put in place, but the notion that is being just stirred so vigorously…it's just a lot of smoke and mirrors. It’s not an argument or set of arguments. It’s not meant to last.”

A spokesperson with the WIAA said it does not actively track the specific number of trans athletes competing in Washington schools, but the association is aware that “there are and have been athletes competing.”

Roxana Gomez, youth policy program director at the ACLU of Washington, explained that, in her area of law, few things are as cut and dry as including trans kids in Washington school sports, which surprised her. The Washington Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) reinforces the WIAA standard, and if schools want to participate in the league, then they’ve gotta follow the rules.

Now, reader, if you’re angrily tapping out a jab about trans women’s definitive athletic advantage, then save your fingers, as science does not support that claim. Doctors who study transgender medicine say athletic institutions are putting the cart before the horse, excluding trans athletes from play before there is a robust body of evidence to support claims of their athletic advantage.

Some studies suggest the opposite. A recent cross-section study funded by the International Olympic Committee and published in The British Journal of Sports Medicine found trans athletes were at a disadvantage when compared to cisgender athletes. In 2017, another leading journal published a literature review that found no “direct or consistent research” showing advantage. One 2023 study in Frontiers Exercise Physiology found that hormone therapy “reduced, if not erased,” sex differences in transgender patients over time. Limbs aren’t going to shrink on their own, but we’re not measuring cisgender wingspans, either.

Outside of policy at the school level, queer legal advocates said the Washington Law Against Discrimination is on the side of trans athletes.

Denise Diskin, co-executive director of the QLaw Foundation of Washington, said the WLAD does not directly address athletic participation, but it does protect gender identity and expression under the banner of sexual orientation.

The law, which lawmakers wrote in 2006, states that anyone having or being perceived as having a gender different than the one a doctor assigned them at birth had the right to be free from discrimination. Diskin explained the law's broad language applies in situations with cis, trans, gay, or straight people. Any person can be punished for falling short of traditional gender roles, like a cisgender woman whose employer thinks she dresses too masculine.

According to Diskin, the law led to several cases around professional attire, but there is little case law when it comes to the WLAD and trans athletes in Washington. For legal interpretations, lawyers are dependent on the WLAD and the Washington Administrative Code’s inclusive handling of gender-segregated facilities.

“I think Washington law is very clear that forcing trans athletes to play on a team that doesn’t meet their gender identity and expression is unlawful,” she said. “Now, does that mean that every league in Washington is going to follow that rule? No. Because honestly, if people always follow the law, then I would be a flower arranger instead of a lawyer.”

Diskin said the law is less clear when it comes to member-organizations and pay-to-pay leagues. Colleges are another concern.

In April, the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics voted to ban trans athletes from competing against women, a decision that affects roughly 83,000 athletes at 241 colleges across the country. One of them is Evergreen State College in Olympia.

A spokesperson for Evergreen said in an email that it is working with the Attorney General’s Office to see if the NAIA ruling conflicted with the state’s anti-discrimination law. (When asked about potential conflict, the AG’s office said in a statement that it did not interpret state law outside of its official processes).

While the NAIA ruling did not impact any current student athletes at Evergreen, the college’s director of athletics, Elizabeth McHugh, said in a statement that the department felt deeply disappointed in the NAIA’s vote and remained committed to advocating for policies that uphold the rights of transgender athletes.

The NAIA ruling has no bearing on big state schools such as the University of Washington and Washington State University, both members of the National Collegiate Athletics Association. The NCAA has its own problems–and higher stakes. Its decisions affect half-a-million athletes at 1,000 colleges and universities, but only about 40 of them are known to be transgender.

Two years ago, the association swapped its long-standing policy of allowing trans athletes to play for the non-policy of deferring to the international guidelines of each individual sport. For sports without international guidelines, the NCAA looks to the Olympic Committee for rules.

The NCAA decided to implement the changes slowly, and by next school year the process will be complete. At its end, trans women will be banned from NCAA swimming, diving, water polo, cross country, cycling, and track and field–indoors and out.

Transgender athletes and their allies worry the NCAA could go the way of the NAIA. As the NCAA hosted its annual Inclusion Forum in Indianapolis last month, 400 current and former collegiate athletes, researchers, and civil rights groups sent a letter begging the association to allow trans athletes to play. On the other side, a group of cis woman athletes sued the NCAA, claiming transgender participation actually violated their rights under Title IX. The NCAA said its policy is still under review.

Gee, Joseph, that Title IX update sure would help alleviate all this confusion!