In a back room on the first floor of the Henry Art Gallery, there is a disco.

It isn't an average disco. There's no hairspray, neon lights, or shimmery dresses, but in the darkened gallery, the sounds of soul and R&B filter in through speakers. The most notable feature of this disco is its stand-in for a disco ball: a rotating lantern of alternating designs from artists Barbara Earl Thomas and Derrick Adams. The panels from Thomas feature meticulously cut-out images, with items you might need for a night out on the town—an afro pick, pocketbook, dancing shoe. The panels from Adams consist of abstract designs, a geometric jumble. All cast long shadows across the room as the lantern spins.

This gallery is the pinnacle—or the "guts," as Adams called it—of their joint show, Packaged Black, up at the Henry Art Gallery until May 1, 2022. The exhibition explores the influence of Black culture on commerce and representation and how Black folks present themselves to the world every day. Featuring all-new work from Thomas, including an immersive "Transformation Room," the show is spread across several galleries on the museum's upper floor. Adams and Thomas show pieces both side-by-side and separately. Packaged Black feels cohesive despite the artists' different methods, with their interests in Black history and self-presentation giving the show a strong undercurrent.

The duo first met at the opening of Jacob Lawrence's Great Migration series at MoMA back in 2015 and again at a seminar for Lawrence's 100th birthday at the Savannah College of Art and Design. It's hard not to think the spirit of the modernist painter and icon blessed their friendship. In a recent interview with The Stranger, Thomas said there was an immediate "family-like feeling" between the two artists. And after getting to know each other better, Thomas said she was keen to bring Adams' work to Seattle, believing it to be a "good injection of energy" into our arts scene.

She was right. Across several galleries on the Henry's upper floor, Adams' spray-painted sculptures, vibrant collages, and thoughtful video works collectively embody a singular and energetic approach to Black cultural production, emphasizing abstract forms and bright colors. Adams' work differs significantly from Thomas' intimate and intricate cut-paper approach to portraiture and sculpture. To make sure they were on the same page, Thomas told me they corresponded via email throughout the pandemic, slowly shaping what the exhibition would look like inside the museum.

Perhaps where the thematic thrust comes together best is in the show's central gallery, which contains the works of both Adams and Thomas. When you enter, a selection of life-sized portraits from Adams' Style Variation series greets you on your right. Adams has based each portrait on mannequin heads at Black beauty supply stores, who dutifully model brightly colored wigs in different hairstyles—red' fros, green tresses, blonde braids.

These figures can instantly be read as a celebration of the art of Black hair, but there's something that pulled me deeper. While their facial expressions reflect the serene anonymity of a mannequin, their watery eyes communicate a specificity, as if Adams gave each head its own backstory. At a bigger-than-life size, these faces seem to float, peering down at you, like they know something you don't.

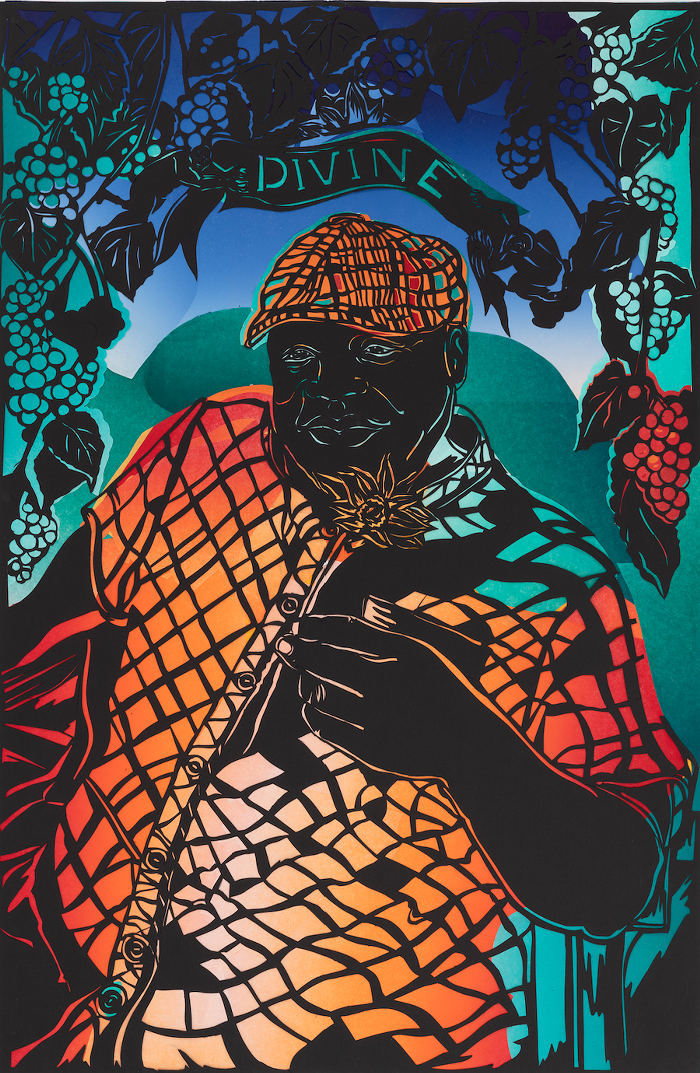

Adams' paintings contrast with Thomas' highly-stylized portraits of Black colleagues and friends on the other side of the gallery. The most striking is titled "Delicious," which remixes of a portrait of Dandy—creative partners David Rue and Randy Ford—originally captured by Seattle artist C. Davida Ingram. Thomas' rendition places Ford and Rue's embrace against an epic landscape with a mountain looming in the distance. The lines composing their features, garments, and bodies are delicately cut from black paper that overlays a creamsicle background.

Another highlight is Adams' ode to the queer Black designer Patrick Kelly. He took the fashion world by storm with his vibrant patterns and provocative designs before dying at 35 of AIDS-related causes. Adams told me he spent months going through Kelly's archives at the Schomburg Center in New York, looking into Kelly's personal history and clothing patterns.

From there, Adams created Mood Boards, on view at the gallery, paintings that reference garments and dress patterns. He's installed some so that you can walk around them like sculpture. These pieces are "totally influenced by the language of fashion, but also abstraction," said Adams, rearranged to "talk about form and structure as a fine artist." And you can see how Adams married Kelly's love of bright polka dots with his own penchant for geometric color-blocking, interlocking a garment form with that of a painting. It's an exciting translation and tribute to the work of a Black icon gone too soon (and seems especially pertinent after the similarly tragic death of fashion designer Virgil Abloh this week).

Greatly inspired by Adams' work with Kelly, Thomas said their discussions around garments had her reflecting on the dreams and visions that make fashioning objects possible. For her, that meant creating her own royal court made of friends and colleagues, as well as her own version of Cinderella's dress. And while the dress is certainly A Moment in the main gallery, seemingly floating in the air, I found greater solace in her cut-paper portraits of her so-called court, hung in a mint green gallery.

“The whole idea of taking Cinderella and the court and all of the courtly life—I wanted to say, in my world, all those things exist, except they exist in a little bit of a different configuration," Thomas told me.

She's dressed the men that compose her court in everyday clothing, but added something princely: a hummingbird attending to a curl or a touch of royal blue in their coat. It's all a reference to how court members signified their position through clothing, but it's grounded in the spirit of how Black folks often present themselves to the world: regally.

Packaged Black runs until May 2022 at the Henry Art Gallery.