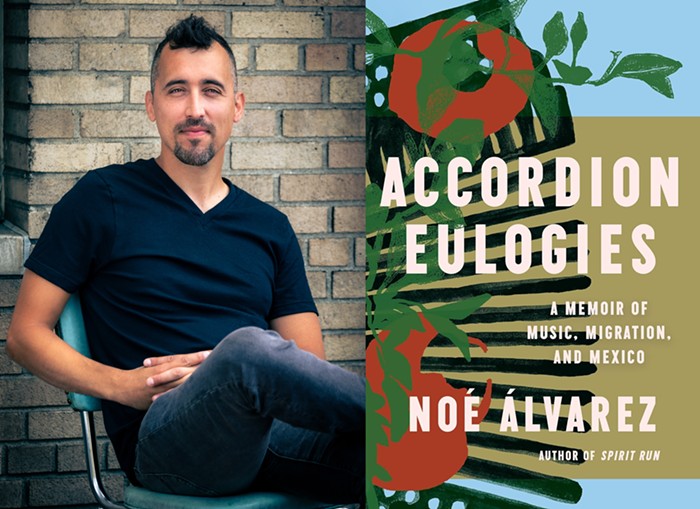

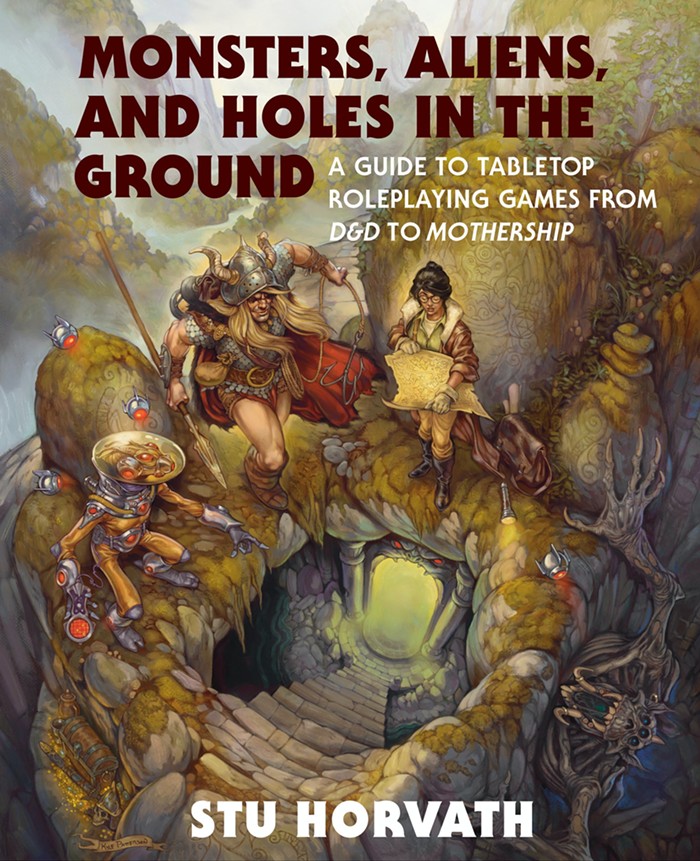

Six years ago, an Instagram account launched with a darker version of “daily affirmations” than you might expect amongst the site’s usual mindfulness incantations and baby-animal memes. @VintageRPG posts one picture a day, every weekday, of a different nerdy tabletop game—think Dungeons & Dragons (now a Seattle-area institution), plus other imagination- and dice-filled games with ties to the Pacific Northwest (Vampire: The Masquerade, Shadowrun).

Each picture is taken by New Jersey journalist and critic Stu Horvath, and stunningly, each is sourced from Horvath’s own personal collection, suggesting that there’s a storage unit somewhere in Jersey that's bursting at the seams with enough demons, trolls, and horny near-future cybercrime to scare the wits out of namby-pamby Baptist parents.

This month, Horvath’s collection of high-res photos has been translated to a handsome, 438-page hardcover book, titled Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground. Each entry appears in chronological order with Horvath’s own historical context, research, and anecdotes, and the result is arguably the most comprehensive historical telling of the American tabletop gaming scene ever made. If you don’t have time for that kind of shit, well, there’s an Instagram account for you. But I’m charmed by how Horvath’s figurative shelves of books, boxes, and beasts, as combined into a single book, represent the hobby far beyond the D&D empire currently run out of nearby Renton, WA.

Thus, I’ve collected a few of the book’s most tantalizing stories as a tiptoe into the world of Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground.

Parental Guidance Strongly Recommended

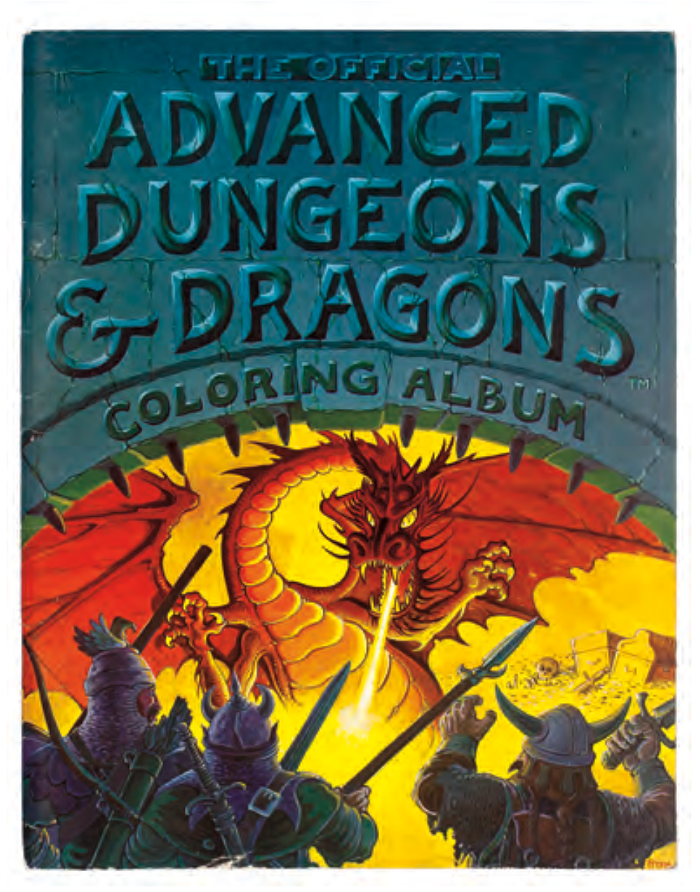

Once the Satanic Panic took hold in the early 1980s, terrified parents were quick to judge anything that hinted at devil worship. The original handlers of D&D didn’t help matters when they stoked the imaginations and fears of children with The Official Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Coloring Album in 1979. This freakish collaboration between D&D co-creator Gary Gygax and an original animator of the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine descends into violent chaos, complete with Tiamat, queen of evil dragons, leading the murderous charge against the book’s main characters. “Several of the adventurers die,” Horvath writes. “This is a children’s coloring book.”

Unsurprisingly, many unwitting parents bought this book for their kids, who gobbled up the violence and discovered a miniature how-to-play guide tucked into its pages. Find any old fart who still swears by the oldest-school D&D products, Horvath suggests, and you’ll probably find a chance childhood encounter with the Coloring Album.

Gygax’s Best D&D Secrets May Have Died with Him

In Dungeons & Dragons’ earliest days, co-creator Gary Gygax would host his own games and serve as their Dungeon Master (DM), sending his players (including his own children) into a dangerous castle dubbed Greyhawk. Gygax and his collaborators went on to mention and tease this fictional world’s existence in tabletop guides and magazines of the '70s, which led readers to beg for a version they could buy and use in their own games.

As Horvath tells it, Gygax was itchy about obliging his fans, because if he wrote a comprehensive guide to his Greyhawk world, then anyone—including his own players—might learn what secrets he’d built into the castle’s walls, traps, and depths. (DMs are like magicians this way, as far as keeping their secrets.) Instead, he wrote a limp series of Greyhawk-branded rules and guides, and each was related to his homegrown castle in name only, prompting fans to complain about the Greyhawk books and guides being “too vague.” This disconnect admittedly led to a wackadoodle World of Greyhawk years later, divorced from any hope that Gygax would tell his full home-table tale, with groan-worthy jokes and puns and nonsensical, unlicensed “villains” like Dr. Who and Colonel Sanders, all leaning into the joke of the series’ constant disappointments.

Decades later, Gygax moved forward with a plan to finally reveal his version of Greyhawk, only to suffer multiple strokes and bow out of the project before his passing in 2008. No trace of Greyhawk was ever released by Gygax’s estate.

Dungeons and… Dallas?

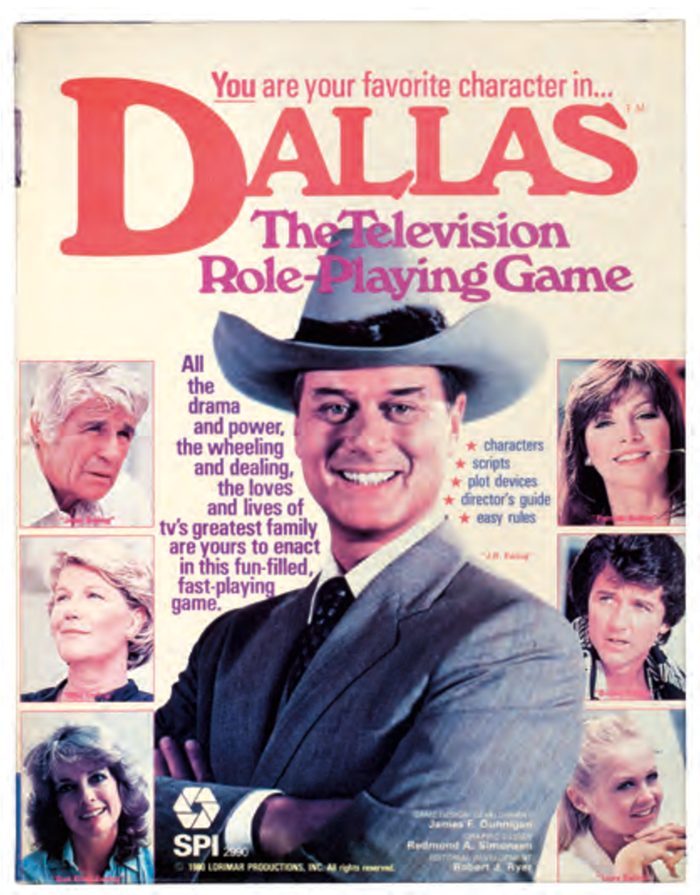

Horvath’s book chronicles hundreds of “role-playing” tabletop games, most of which have zero official affiliation with D&D. The most interesting subgenre sprinkled through the book’s 49 years of history might very well be the pop culture tie-in game.

This book draws a line between bonafide role-playing fare and simpler, licensed board games, leaving out the admittedly WTF board gaming likes of Full House and All My Children. Its weirdest example is Dallas, which revolves entirely around players pretending to be characters from the hit TV show while engaging in entirely new, drama-filled storylines about prostitution, hostile corporate takeovers, and federal indictments. In a telling quote, Horvath cites one of the game’s creators to describe a disconnect between that era’s biggest tabletop fans and this bizarre licensing mash-up: “[We printed] 80,000 copies [of Dallas]. That was about 79,999 more than anyone wanted.”

Fuck HP Lovecraft

One of the biggest role-playing series outside of D&D, Call of Cthulhu, established an entirely new way to add horror to tabletop games beginning in 1980. It stood out at the time, and continues to enjoy a large fanbase, due to how it invited the inevitability of terror to the gaming table via its creative rules. But, well, it drew from HP Lovecraft—and you don’t need to look far to find reasons to kick that bigot to the tabletop curb. (Content warning: extreme bigotry in many examples here.)

Should you wish to appreciate this long-running series’ innovations with a somewhat clearer conscience, Horvath gives you a few outs. For starters, Call of Cthulhu publisher, Chaosium, “has moved to become increasingly and explicitly anti-racist, disavowing Loveraft’s bigotry in public statements.” The official game’s modern resources live up to that standard for the most part—as does Delta Green, a legendary Call of Cthulhu spinoff co-created by former Stranger columnist John Scott Tynes. Still, Horvath does you one better by recommending resources and spinoffs from the past decade made by Black and LGBTQIA+ creators. These include Masks of Nyarlathotep, Harlem Unbound, and Berlin: The Wicked City.

Also, Kind of Fuck Gary Gygax

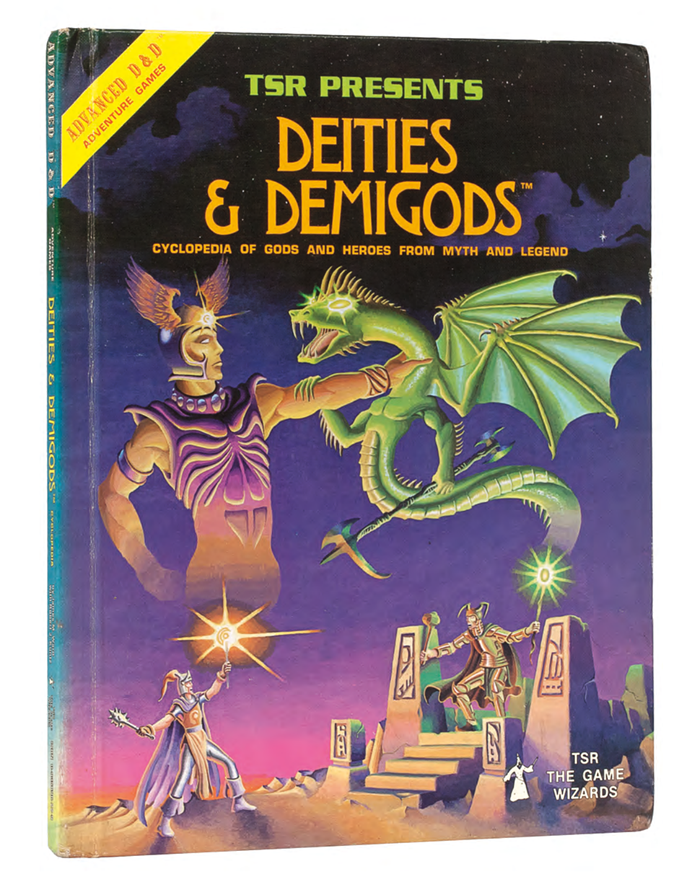

D&D’s original publisher, TSR (short for Tactical Study Rules), neared financial ruin multiple times before melting down and selling to Renton’s Wizards of the Coast in 1997. Horvath notes that 1984 saw the publisher in dire financial straits, fueled in part by “spending money on everything from a fleet of employee cars to purchasing an arts and crafts company, to raising a shipwreck.” Horvath says its finances turned around when Gygax returned from a Hollywood trip to publish a new subset of D&D rules, along with an expansion book titled Oriental Adventures.

A book in 1985 with a title like that? You bet it was a mess, rife with “lurid pulp stereotypes, Yellow Peril propaganda, and the lingering specter of European imperialism.” Horvath also describes the book as a “monolithic mush of fantasy ‘Asianness’ that verges on parody,” capitalizing on “America’s pop cultural preoccupation with all things Asian during the '80s.” Which means, yep, it was a rousing commercial success, and the book even saw a re-release from Wizards of the Coast in 20-fucking-01, touched up to reflect updated D&D rules but not updated social norms.

A D&D Revival with the Unbecoming Stink of Capitalism

Once Wizards of the Coast took over the official Dungeons & Dragons series, it moved forward to create an entirely new ruleset, D&D Third Edition, which was first published in 2000. It was an unsurprising move from a company eager to squeeze more value out of its newly acquired property. But rather than chronicle how the series grew and changed, or what kind of creativity it fostered in its new ruleset, Horvath focuses this section’s historical text on corporate overreach in the form of the “d20 System trademark.”

In short, d20 (named after the hobby’s popular 20-sided dice) was meant to offload the writing-and-publishing burden of supplemental materials to third-party publishers, who would then pay WotC a tidy licensing fee to pull their new books and guides up to the potentially lucrative D&D3E buffet table. Ideally, this would all keep existing fans satisfied, bring new fans into the D&D fold, and let WotC efficiently rake in the resulting cash. Horvath’s explanation of what happened from there is an unsurprising economic breakdown of supply and demand, albeit with a sprinkle of “nudity, graphic depictions of sadomasochism, and demons galore.” Between WotC’s capricious handle on the d20 System trademark’s rules and restrictions, and the company’s eagerness to create new products that broke the old books, participating partners found themselves wondering whether the highest fantasy of the genre might not be devils or vampires but rather staying the hell in business.

Instead of chronicling WotC’s fraught D&D Fourth Edition, then, Horvath’s book instead describes and celebrates the far more popular Pathfinder series. This 2009 ruleset picked up where D&D3E left off and better served that ruleset’s more faithful lovers of many-sided die and carefully painted miniatures, and Pathfinder’s popularity persists to this day.

Sick Art That Rivals the Best Metal Album Covers

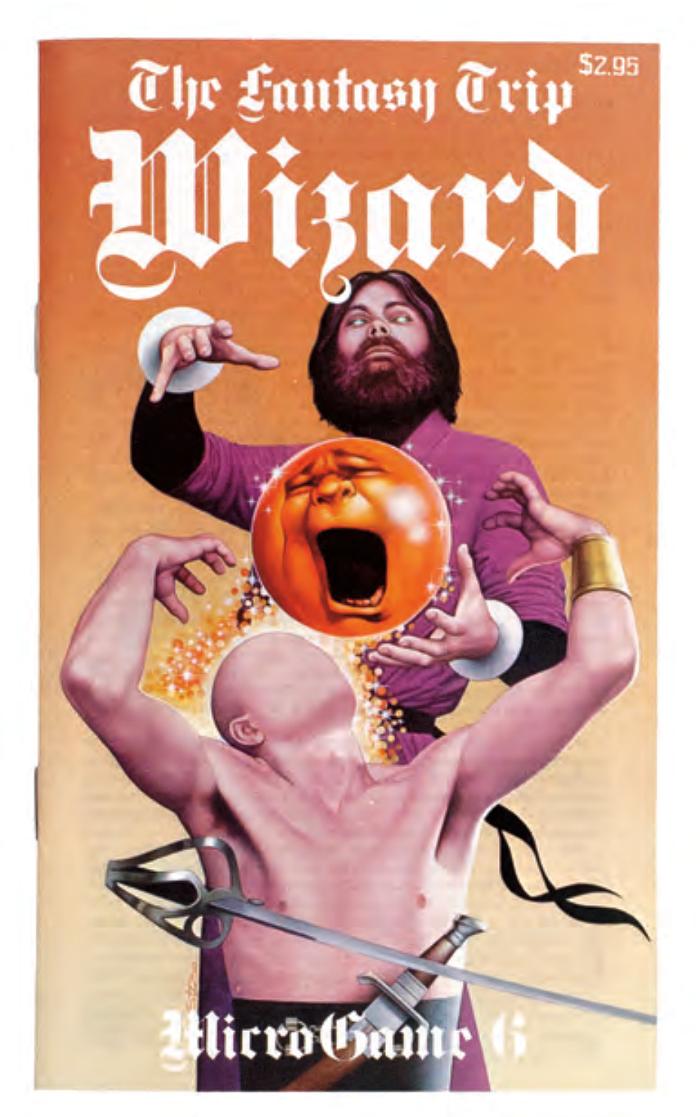

If you take nothing else from this book, perhaps en route to clicking through Horvath’s associated VintageRPG Instagram account, it should be the Tolkien-obsessed artists who assisted the earliest and most pioneering D&D-like games. Late '70s series The Fantasy Trip in particular includes some of the most nightmare-inducing art, like this cover from artist Roger Stine that depicts a wizard trapping a shirtless man’s agonized face inside a floating orb:

I’m also partial to this horny-looking embrace, where a Grecian-styled superhuman strokes a dragon’s neck while the dragon, in kind, caresses the person’s forearm—all posed, of course, atop some kind of laser fight between two completely different people in gladiator-ass outfits:

The whole book is a fascinating tiptoe through each decade’s hella-nerdy art inclinations: fantasy versus sci-fi; realism versus surrealism; starry-eyed primary colors versus more grim brown-and-red palettes; massive dragons versus icky spiders. Horvath’s own photography does each of his relics artistic justice, with some arguably looking better because of years or decades of wear and tear. (One thing you can’t properly savor on Instagram is the brand-new art made for this book by UW graduate and Washington State resident Kyle Patterson; his own Instagram is a good indicator of the nerdy art cred he brings to bear.)