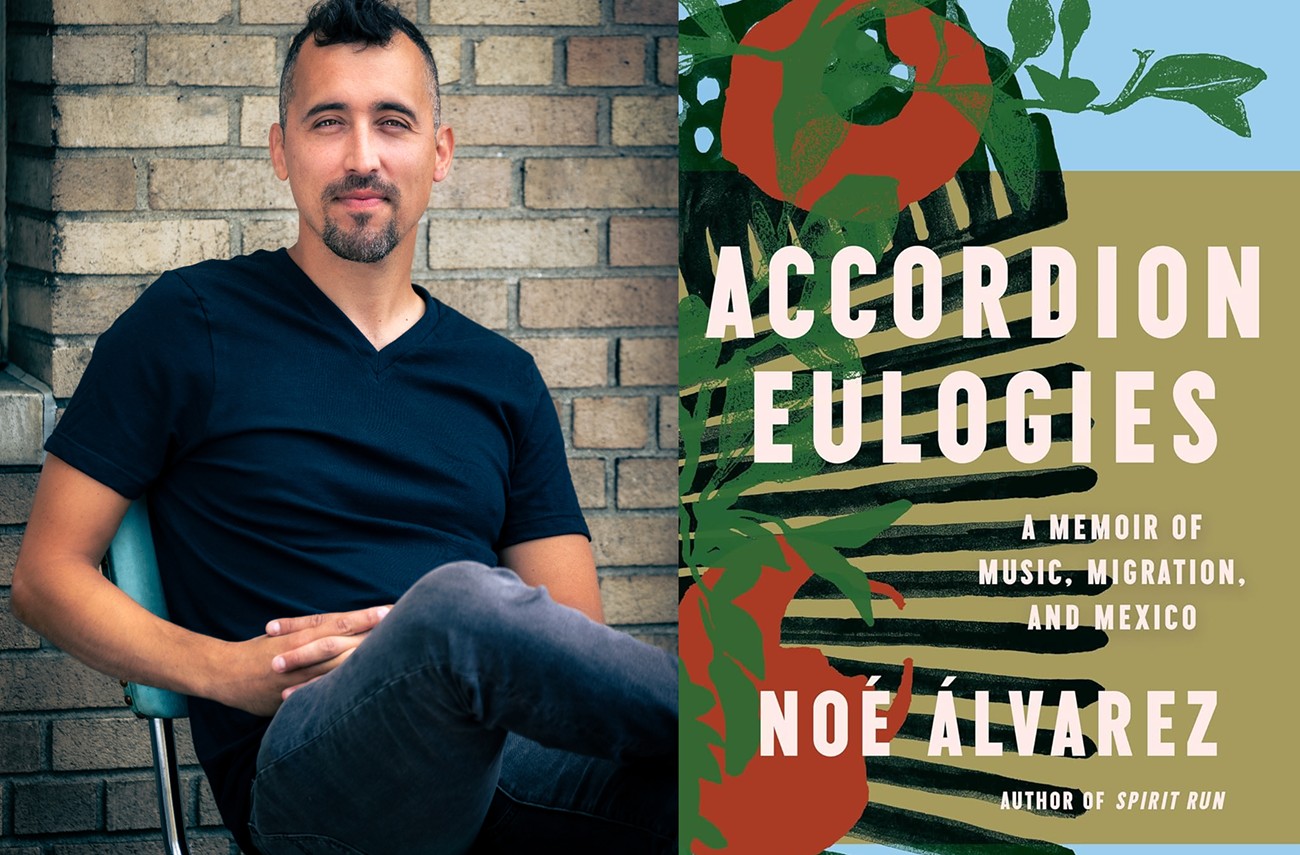

It’s hard to categorize Accordion Eulogies by Noé Álvarez in genre-stable terms. Wisps of memoir, musical theory, travelog, political treatise, and dirge combine to spawn a searing commentary on neglect and healing and belonging. Immersive beyond words, it’s even got a playlist to accompany its punchy prose.

At its core, Álvarez’s second book is about a haunting absence. His paternal grandfather—named Eulogio (eulogy)—abandoned Álvarez’s father growing up, leaving him to face homelessness in Mexico. With Eulogio no longer around, cautionary tales about him took his place. Some stories about Eulogio, however, praised his dexterity on the accordion playing corrido music: sweeping ballads about oppression and existential struggles.

By encountering accordion players spanning the globe, and by picking up the instrument himself, Álvarez uses the accordion to learn more about his grandfather, himself, as well as the myths cursing his family.

In an interview with The Stranger, Álvarez, the Yakima-born and -raised son of farmworkers, explains the stakes involved in his search for truth, reflects on the interplay between death, catharsis, and birth, and interprets the accordion as a writing utensil.

The pursuit at the core of your book seems like something you were willing to put your life on the line for. In the last third of your book, you're navigating cartel wars and state violence and industrial violence and so forth, all to reach your grandfather in Michoacán.

I appreciate that. I hadn't really thought about it like that, I guess. I felt like I was part of this journey whether I wanted to be or not, like I was a part of something bigger, and I was just trying to look for a way to articulate what it all meant. A lot of my life was geared towards running away or turning away from a certain pain or a certain past, and I think, with this music, with this instrument, I just felt a little bit more empowered to confront it.

I told myself that I needed to go through with it to find closure, however much I could find. Maybe on a superstitious level, I felt like I needed to do something with this past. The landscape itself has such a hold over our family, over our narrative spiritually, historically; it continued to rear its head even more strongly over the years. And having not confronted it all my life, I felt that if I didn't do something about it, I was maybe going to crumble in some way. And I didn’t want that, and so I thought that maybe I could bring some healing to the story, and pass that down to my child. When I got to a certain stage in Mexico, I just felt like there was no turning back, like I was a part of this momentum that I couldn't escape.

I felt like there was a curse on the family, and I thought that maybe part of that curse had to do with the fragmentation of our story. And maybe I needed to go and collect some more stories, collect some more experiences so that I could maybe assuage some of this or some of the spirits in the ancestral home of my family. If [in the end] it meant turning my back on it for good, at least I could know that I tried, because I think part of the trauma is knowing that you could have done something more but didn't. So I didn't want to carry that baggage with me. I knew I could still reach out to this relative of mine, and I wasn’t going to be able to look myself in the eyes if I didn't do this.

A throughline I identified over the course of reading your book is this idea that death will happen and in some ways you get to choose it. Some of the deaths you were affected by in Mexico were very sudden, for instance, or were more languishing in the United States, the death of being removed from the place you’re from. After meeting your grandfather, you mentioned how you felt like a part of you had died, but maybe sort of in this cathartic way. You made this effort to try and find this meaning and closure—and regardless of whether or not that happened, there was still some growth or birth that came out of that darkness. I don’t know if that resonates at all.

It's definitely true. I titled the book Accordion Eulogies because I was learning how to eulogize the things in my life currently and in the past. There was an aspect of sacrifice that I was kind of embarking on. I needed to confront these stories and surrender myself to the land and the stories as authentically as possible. I needed to see things die on their own, I needed to see things exist or fall away.

When I saw my grandfather—which I won't go too much into because that’s in the book—I had to choose between a fast death or slow death. That's where I feel like I exist. I structurally see and symbolically see my instrument, my accordion, embodying these different realities of mine. The accordion in music embodies so much death, and the music can be both depressing and enlivening. The lyrics in corrido music contend with death, people who are just taking it a day at a time, and so there are lessons in that for me. Maybe I just needed to musically hear what was inside of me and experience the texture of the land.

I'm a writer and a lot of it is silent work, and I find a peace to that, but musically, lyrically, I didn't know what the sounds of agony sound like. And so the accordion was the instrument that really pulled out those emotions. A lot of the men, especially, that I interviewed were like, “This is my way that I mourn, this is the only way that I know how to cry.” In my very cowboy-tough tradition, you're not taught or encouraged to cry, and the only times were during this kind of music, corridos and so on. So I thought, okay let’s tap into that a little bit more and see what I can do with it.

Why did you include a playlist at the end of the book?

It was to show what I'm trying to do with writing and what writing means to me. I’m very much community-oriented. I'm a firm believer in giving back. I couldn't have written any of my books without others—without my parents, without the musicians in this book. I structurally wanted to show that by writing chapters about them. I wanted to cross-promote.

I originally intended to have QR codes in every chapter so that readers could listen to the music as they're reading about a specific artist and so that spiritually, audibly, they could become submersed in the story as they're reading, but we decided [on one playlist at the end of the book]. I didn't grow up with reading as a culture, it was a luxury in my life. I'm visually oriented and also understand that words aren't necessarily the most accessible to people, especially my parents. So if, at the very least, I can guide them towards the QR code and invite them to just listen to that, then I've made the book more accessible to people like my parents and people who don't read.

I am trying to honor the other musicians who shared some really awesome things with me, who opened their hearts to me, and so it's a collaborative thing. That's how I see myself as a writer: I'm always bringing in the people who matter to me and have had an effect on my life.

What was the process of writing about music like?

It's funny, when I ordered this instrument from Castagnari in Italy, I asked them to recommend the saddest instrument they had. I wanted to tap into my soul, I wanted to maybe find some power and give it some sound. I would sit for hours [playing the accordion], sitting with those beautiful sounds, feeling those vibrations in my chest, and then just let it introduce thoughts into my head—stories and memories—and I would close my eyes. And it would take me to specific memories of my family and my upbringing. And then I would write those stories as a result of playing this music. And then when I’d sit with musicians who played music in front of me, I would ask them to play music, and seeing them play would provoke memories. And then they would share very personal hardships about what that instrument means.

Speaking of emotions, I'm curious what your relationship to Yakima is like now. Toward the end of your book, you say you have to believe that things are headed in the right direction in Yakima, despite your experiences there growing up, and despite the visual markers of poverty and struggle you continue to see during your visits. Have those feelings changed at all since the book came out?

I think that is still where I'm at today. The story of that land was always rearing its head, it was always coming out of my writing and coming up in my conversations, coming out in my nightmares. It was always there, so I had no choice but to turn back. Especially now that I have my two-year-old, I want him to have a different mentality and a different approach to wherever he goes, because it's only going to be a matter of time before he decides to embark on his own crazy journeys.

The reason I have to believe Yakima’s in a better place is that it motivates me, it gives me hope to work with it more, work with the people, and so it gives me maybe a little bit more courage to go back and do things differently. For instance, growing up, we didn’t have the luxury of pursuing some of the trailheads that are around there. My parents already worked 10-, 15-hour jobs in the fields. To then say, “Hey, do you want to go walk as exercise for fun in addition to that?” was crazy talk. Similarly, I remember the first time I told my dad that I went to a U-pick farm where you pay to pick fruit, and he said “You did what?”

The lessons my father gave were mainly about escaping Yakima and getting out of there. And he was right. Part of me does believe that Yakima, one day, on a superstitious level, will be the end of me. I can only stay there for a weekend; any longer is still very, very difficult for me, because I continue to see and feel even more emotion around the things that haven’t changed or have gotten worse. So when I see those things, it's hard not to take it personally, it clouds me and affects my work. And so, unfortunately, I still have to maintain my distance.

You wrote in the book how you wish you had the resources to buy up an orchard and let it lie fallow, turning it into its original ecosystem over time. And it's interesting, like, with the resources you have, how you're still sort of trying to nurture that but maybe in a slightly different way.

It’s an effort to restore and reconcile our relationship with the land. I wonder why there are so many deaths in Yakima. That's why I'm a little superstitious about that. My dad tells me there’s an element there that just feels haunting. Some traditions ask the ancestors for permission when you enter a land, and I’m wondering if there have been violations with us as a people either harvesting the land or just coming at it and assuming we’re the rightful owners of the land. What are we doing to speak to the history that's happened to that land?

When I think about the orchard, there’s just so much mixed baggage. On the surface, it’s beautiful, and it does provide food for people, but I see it from the other way around. I see it from the inside out. And I can't help but still feel devastated by that, and I see more warehouse labor too, and it seems like there’s maybe no way out of it. There's some distance there between what the people are deciding is necessary for the world and what the land is experiencing. And as a result, it's taking a lot of our people, taking us into the soil. There's so much hurt in the soil. I'm trying to address what's in there before I, too, am taken down there. Before my parents are taken down there, I'd like to know how to mourn that. I'd like to have a home and not break into pieces when my parents depart. I’m just trying to start up a conversation a little bit more realistically in Yakima.