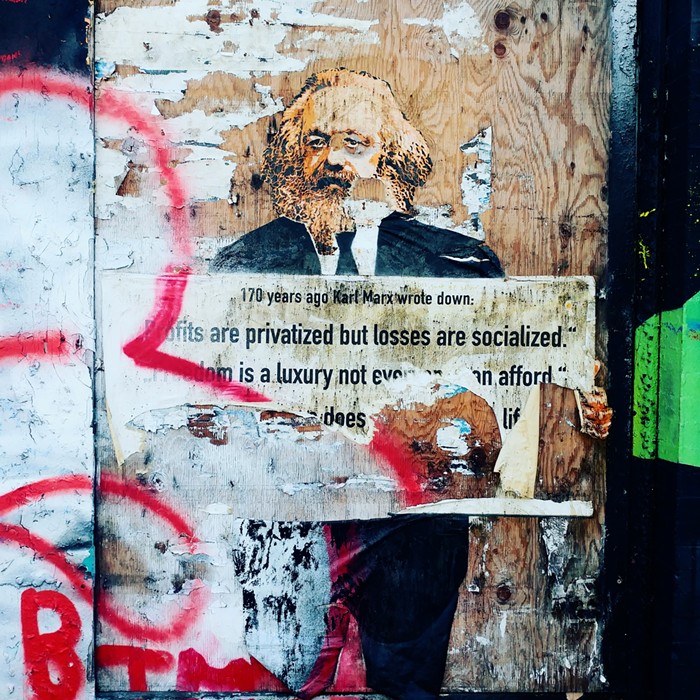

I found it among my things while sorting laundry: a t-shirt of Marx partying with Mao, Lenin, Stalin, and Che. I knew it was my daughter's. She is 17. It was time for me to have that talk with her. She needed to know truth about socialism, and how it relates to Marx, and why, as an economic project in the 20th century, it mostly failed in both the East and the West. I texted her. Asked her about the t-shirt. She texted back: "Yeah, I found it at the Goodwill." I asked if she understood what it represented? She texted: "I thought it was funny LOL." I see. Well, it's not all fun and games. It is, in fact, something important that we need to discuss. You see, you grew up in a world that emerged not only after the collapse of socialism in the East, but also social democracy—the capitalist compromise with socialism—in the West (also known as Keynesianism—I will talk to you about John Maynard Keynes, maybe the most important economist of the 20th century, if you happen to find and buy a t-shirt of him partying). Your world is similar to the one I was raised in, in the sense that government is still huge. This was not the case in the 19th century, the period defined by the consolidation of capitalism and liberalism (liberal, not as in the left or progressive politics, but as in free market and free trade ideology).

Back then, the liberal moment, governments were smallish. After World War II, they grew tremendously, often with budgets exceeding 50 percent of the GDP (this may surprise you, but government expenditures in the liberal moment were around 10 percent of the GDP). At first, a generous portion of this spending supported social democratic programs that were demanded by a public that had experienced the horrors of two capitalist wars, World Wars I and II, and still had painful memories of the Great Depression, a situation where idleness was politically imposed on capacity (the means to make things and generate employment), a madness within a madness. Many at this time thought liberalism (or laissez faire) was done for good. In the US, there was the New Deal; in the UK, there was the Beveridge Report. The Soviet Union expanded its sphere of influence. China went red. And much of the post-colonial world was non-aligned. Governments at all stages of development played an active role in the management of their economies. For developing nations, infant industry polices, import substitution industrialization, capital controls, and the like were in vogue.

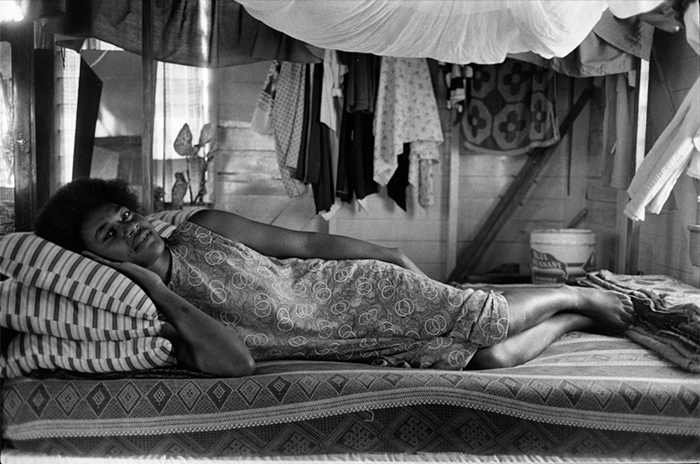

But did this new order (social democracy and socialism) resolve the crises of the 19th century (blunt and often brutal class struggles and economic busts), which resulted in the catastrophes of the first half of the 20th century? Social democracy was partially successful, but it was also never really politically secure. Its whole existence depended upon, not its ideals (welfare benefits, universal health care, public housing, Keynesian expenditures—building bridges and dams and what have you), but upon capitalists being satisfied with the size of profits. This was the comprise in the West. And it was made possible by the fact that, after the war, profits were exceptionally high in the US, Europe, and Japan (the West). Two reasons for this: on one side, post-war reconstruction projects; on the other, the expansion and growing spending power of the middle class. In spatial terms, this expansion resulted in the suburbs, particularly in the US. This period of rapid growth (sometimes by as much as 5 percent—the average is 2 percent, normal would be 1 percent) is where consumerism as you understand it matured. Its kind (defined as high-income societies) did not exist anywhere in the liberal age. Back then, there was no substantial middle class; you mostly just had poor people and rich people (low-income societies). But, again, the flaw in this seemingly successful system was the nature of the compromise between labor and capitalists; it was based on the size of profits. That resulted in the downfall of social democracy in the 1970s, a period marked by declining profits, saturated markets, and the growing military costs of the Cold War.

But what about socialism, the other response to the class struggles of the 19th century and the resulting capitalist catastrophes? It, too, was a catastrophe, but for a reason most people do not understand. The thing to grasp is this: What exactly is a union? I know you live a world with weak to no labor unions, but when they emerged at the end of the 19th century, unions were a major political force, particularly in the UK, which is where the Labor Party comes from. Unions also had their intellectual roots in the socialist utopianism (Proudhonism in France and Owenism in the UK) that developed in the first part of that century. And this is why the main conception of a socialist society is one that places labor in power.

But again, what is a union? Now, here I need your full attention: It is, in essence, a means by which workers collectively become a capitalist. When their wage-power is consolidated in this manner, they can finally present a real challenge to the ultimate power of the owners of the means of production, circulation, and distribution. Ontologically, a union is a capitalist composed of non-capitalists. This is why, during the social democratic phase, they were politically viable in the West (and can be very conservative—a fact that frustrates many on the left). This is also why they ended in disaster when (as an ideology) they took the form of state power in the East.

The socialist societies of the 20th century were capitalists without capitalists. Meaning, there was no fundamentally (or ontological) difference between them and the West. The fact of this is made clear by the environmental disasters in the Soviet Union and China. Those and other states were not reinventing society, but claiming that an economy run by workers would do a better capitalism than a society run by capitalists. This notion is at the core of orthodox Marxist theory ("the expropriators are expropriated") and is its curse to this day. Orthodox Marxism, therefore, does not represent "a new day." The night of capitalism continues in the form of the labor theory of value, which, in its essence, is tied to John Locke's story of the origins of private property (that will be another conversation we must have). And so, though one system was state socialism and the other state capitalism, the environment could not tell the difference. They were both terrifically destructive.

But 12 years before you were born in 2001, the Berlin Wall came down, and this marked the end of state socialism. And 20 years before that world-historical event, social democratic institutions and programs were demolished aggressively in the US, and slowly in Europe. But did we return to liberalism? I know that's what you must at this point be wondering. Did we go back to the 19th century order of free markets and trade? In one respect, yes, we did. We are now in the second era of globalization and free enterprise ideology, but with a very big difference. The size of government spending has not diminished. But if budgets are still huge and social spending has been cut, what is the government doing with the public purse? It now protects the market from democracy—the demands of workers, or the moral pressures of human rights, or the social costs of environmental disasters. We call this neoliberalism. This is where you are now, in relation to that T-shirt you found at Goodwill.