And so it happened. During the debate, Donald Trump asserted that his opponent, Vice President Kamala Harris, is a Marxist. Why? Because "her father [was a] Marxist professor in economics. [And he] taught her well.”

MAGA, as we all well know by now, loves anything that smells like family dirt. If it's not the sins of the father, then it must be the sins of the son. Because the latter, Hunter Biden, is no longer relevant, MAGA has moved on to Donald Harris, a Jamaican-born economist who taught at a number of top universities, including Stanford, before retiring in 1998. Now, we heard many strange things during this debate, which, to use the imagery of Vivian McCall, the Vice President dominated like "a bullfighter waving a red flag." Some of Trump's claims, such as Haitians eating pets, are beyond me. But not this business of Marxism. Is it true that Donald Harris was (and, one supposes, still is) a Marxist? The answer can only be a resounding "no."

Kamala became visibly defensive and uncomfortable when Trump exposed the truth about her Marxist father to viewers. She wasn't expecting that. pic.twitter.com/TMw5vodL15

— APOCTOZ (@Apoctoz) September 11, 2024

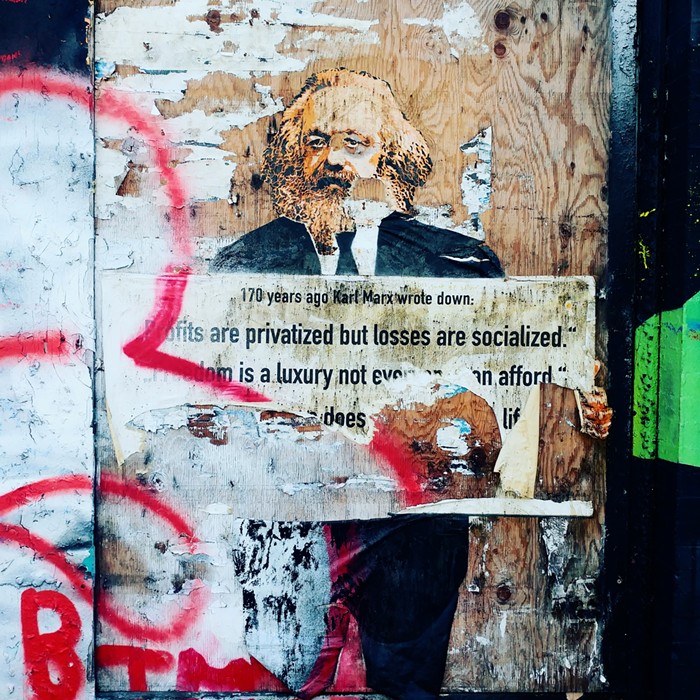

What's important to grasp at this point is Marxism itself. I'm sure Trump has never read even one page of this philosopher's gigantic body of work, which has two eras: the young Marx and the mature Marx. They are very different.

With the former, you do get the revolutionary Marx, the Marx who imagines the specter of communism that haunts the Europe of his youth, the 1840s. In his later years, you get the Marx who almost entirely focuses on the structure, nature, and dynamism of capitalism. This preoccupation defines the three volumes of Capital and his massive notebook, the Grundrisse, which had a lasting impact on the second half of the 20th century.

The later books exerted a decisive influence on Marxist schools in France, Italy, USA, and Japan. The last time Marx's early works were taken seriously by a school was in 1930s Frankfurt at the Institute for Social Research. This institute, also known as the Frankfurt School, primarily examined capitalism from the perspective of its cultural products and their impacts (popular music, cinema, politics, the transition from modernism to post-modernism), forming a branch of philosophy called Critical Theory (yes, that Critical Theory, the denouncement of which became the bread and butter for Seattle's very own Christopher F. Rufo).

But the school also analyzed the economy of its times, which included the years of the Great Depression (1929 to WWII), in a manner that closely resembles what became the dominant form of economic thinking between 1947 and the Nixon Shock of 1971. That movement, which was codified by a conference that took place in 1944 at a New Hampshire hotel, the Bretton Woods Conference, is called Keynesian because one of the conference's key participants happened to be John Maynard Keynes, the author of the most important economics book of the first half of the 20th century, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936).

What the Frankfurt School called post-liberal capitalism is pretty much what we now call Keynesianism. The link is simply this: under the 19th century's liberal capitalism, the state was small and companies were owned by individuals and families; under the 20th century's post-liberalism, the state was huge, and companies were run by managers, by professionals, by investors.

Post-liberalism and Keynesianism are interchangeable. They are defined by an interventionist state and the rising economic influence of consumption. A middle-class is born right here. And, in truth, this is the period of American prosperity that MAGA sees as the home it wants to return to. The America of a large, white middle class that owes its affluence to Keynesian government policies; the state manages the economy, low unemployment and high wages are recognized as tools that dependably keep the working classes away from socialism, and consumption surpasses production in importance. That is Keynesianism.

But what is post-Keynesianism? What is this movement of economic thought that, according to Wikipedia, counts Kamala Harris's father as one of its theorists? To begin with, Keynesian economics split into two schools during the second half of the 20th century. One is called neo-Keynesian and the other is called post-Keynesian. The former is close to what is taught as mainstream economics and is called neo-classical. The defining feature of neo-classical economics is its dependence on mathematics (or equilibrium thinking). Issues of production, distribution, and consumption become nothing but a matter of number. There are no poor, no rich, no workers, no bosses, no women, no men, no nothing but the "rational actor." Meaning, a person whose decisions/motives/actions can be quantified and, as such, predicted.

Neo-Keynesians continue the quantification of economic processes but recognize the importance of distributional factors. They add a little more life, and sometimes even color, to the rational actor. Post-Keynesians, on the other hand, completely break with neo-classical economics. Quantification is not absent from this school, nor is modeling (indeed, Professor Harris was also a mathematician), but it is not central. As with neo-Keynesians, the distribution of wealth is not ignored. But post-Keynesians add late Marx to their analysis of the economic picture. The neo-Keynesians, in line with the neo-classicals, do not. They emphasize instead market failures—for them, there is no such thing as perfect competition. Totally free enterprise is a fiction.

Post-Keynesians, however, recognize class struggle as a real and obvious aspect of capitalist society. Indeed, why do we have unions? Why is Trump trying to get the endorsements of unions? Post-Keynesians are not Marxists, but they do take seriously its analyses of obvious aspects of a capitalist social formation. They also believe that the future of the economy is radically unknown. The future is in fog. No amount of number can make clear what's ahead. Who in the 1960s (even in the 1990s) could see in their models the daughter of a Black-Jamaican post-Keynesian becoming the President of the United States of America?