In the fall of 1992, I answered an ad and received a quick response to be an editorial assistant at The Stranger, "15–20 hours" ("basically we'll take whatever you can give us," I was told) and unpaid ("we can give you a few bucks for transportation and some vouchers for Hot Lips Pizza on the Ave"), and was told not to bring anyone to the office or reveal its location in a Wallingford residence. Not only was a business not supposed to be operating out of the home, but there were some unstable readers out there who might be angry at something published.

In the fall of 1992, I answered an ad and received a quick response to be an editorial assistant at The Stranger, "15–20 hours" ("basically we'll take whatever you can give us," I was told) and unpaid ("we can give you a few bucks for transportation and some vouchers for Hot Lips Pizza on the Ave"), and was told not to bring anyone to the office or reveal its location in a Wallingford residence. Not only was a business not supposed to be operating out of the home, but there were some unstable readers out there who might be angry at something published.

The comedy of my meeting with Christine Wenc (editor in chief) was that she was unduly impressed that I'd had some short blurbs in the Seattle Weekly, and wanted to warn me that I was joining a much-less-respectable operation.

One of my first duties for The Stranger was to corral the music calendar. Along with the personals and classified ads (and graphically interesting covers), a comprehensive and up-to-date culture calendar was one of the consistent pulls for people to pick up the paper. We had one or two always-in-demand fax machines, and I was often reduced to pestering promoters on the phone to get their concert bills—opening acts, set times, ticket prices. KCMU [the pre-KEXP station] had the other reliable music calendar in town—but it was only recited at certain times of the week, and back then, there was no website to check.

As I became the music editor, bands and promoters didn't know me well enough to ask for favors. I was also mostly invisible—though that too was changing, as I'd nearly been assaulted in a bar by one singer over a lukewarm review.

At the start, I sometimes had to beg to get advance or promo copies of CDs from major labels, and was last in line to get interview time. But within a year, we were inundated with CDs, tickets, interviews, and photo passes, along with flattery, pleas, and even mild bribes to get coverage.

Some nights I plowed through a stack of them at the office late at night, and farmed out the rest to the growing cluster of contributors (including current editor in chief Tricia Romano). Other nights I went to shows with sets by three bands. At the Off Ramp, I once stood five feet from an unknown PJ Harvey on her first American tour. When she broke a string in the middle of her set, she went from being a thundering force of nature on the guitar to a shy musician waiting for several agonizing minutes until someone brought her a new D-string.

As a paper, and a music section, we were determined to stay irreverent. We didn't want to spend too many precious column inches covering bands that were already huge like Nirvana or Soundgarden—and if we did, we wanted to offer a decidedly cheeky take on them.

Among the many local acts we covered with affectionate criticism were 7 Year Bitch, the Posies, Love Battery, Sunny Day Real Estate, the Walkabouts, Sky Cries Mary, and the Gits, who I saw play live at the now-demolished venue called RKCNDY ("Rockcandy"). It was as phenomenal as some of the other little-known bands I saw on that stage—Radiohead, Rage Against the Machine. (There were maybe a hundred people at these fantastic gigs.). While many promising local musicians were lost to drugs back then, the warm and charismatic singer of the Gits, Mia Zapata, was murdered while walking home from the Comet Tavern.

After Mia was killed, we covered the many benefit shows devoted to raising money for the investigation, and the Home Alive movement, which grew out of that, to teach women self-defense and provide discussion forums and rides home. Our editor at the time also wrote a critical piece about what she felt were their unnecessarily grim scare tactics.

The burgeoning rock scene meant you were often witnessing unknowns developing into superstars. I once gave a rave review to a record by punk band out of Olympia, Excuse 17, and a few days later the phone rang. Mike Nipper at the front desk told me, "It's Carrie Brownstein from Excuse 17." I picked up.

"Hey," she said, quickly, "That was cool how you described our sound. But listen, that band's finished. I've got a new band called Sleater-Kinney and we're playing in a friend's basement tonight, can you come?"

"Um, sure!"

I was always on the hunt for new writers: The beloved DJ Riz was back on the air at KCMU after the boycott and strike and more popular than ever. I convinced him to write for us—his early columns had an utterly unique and natural blend covering music, language that was musical, food, black culture, Seattle culture, sharp opinions, and loving joy. They were an instant hit.

There was tough competition for space in the section; I tried to balance local bands with jazz and world music acts touring Seattle: Max Roach, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the klezmer revival. I interviewed Tricky, the triphop artist, as we walked up to the now-nonexistent Piecora's. Half of what he said went up in smoke; he sparked up a joint sitting outside right in front of the restaurant. I hired Trey Hatch and he began covering avant-jazz and new genre-free music, including promising local musicians the Young Composers Collective, Gamelan Pacifica, Stuart Dempster, and Wally Shoup.

Often people will ask if I met Nirvana. While I later met Krist Novoselic during his work against censorship, and informed Dave Grohl about Dan Savage's crush on him, I only had one encounter with Kurt Cobain: at Ernie Steele's Tavern, where he was drinking with Courtney Love and Mark Lanegan. As he was standing alone by the jukebox for a moment, I introduced myself and tried to hit him up to do a guest column for us. "The Stranger," he said, reflectively. "You guys have some really cool artwork." I never got that guest column.

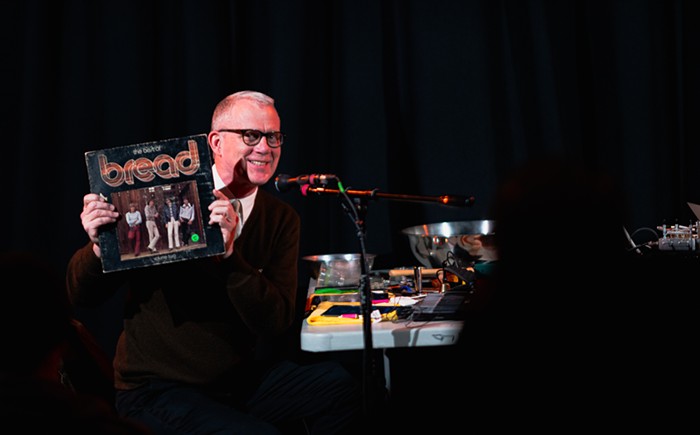

Danny Housman was the music editor from 1993–1996. He is a writer living in Los Angeles and host of an "intellectual salon" speaker series, and has been active with NewGround: A Muslim-Jewish Partnership for Change. ![]()