Jen Graves shared more thoughts about The Queen Protester on Blabbermouth, our week-in-review podcast. Subscribe here.

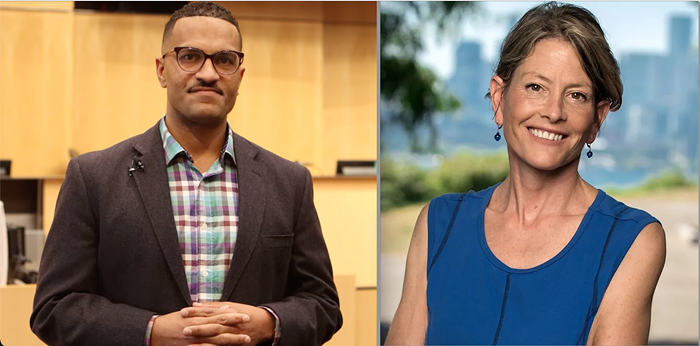

Looking at all the photographs he took at the Baton Rouge Black Lives Matter protests on Saturday, Jonathan Bachman knew right away which shot was the shot.

And zam, it went viral.

The way the freelance photographer for Reuters saw it, the woman, whose name he didn't get, "was making her stand," he later told The Atlantic. "To me it seemed like: You're going to have to come and get me. ...It's representative of the peaceful demonstrations that have been going on down here."

One commenter on the original Reuters Tweet hissed, "Looks more like dressed up for her minute of fame."

Yes. And?

Bachman never met the woman and didn't get her name. But by chance, the woman in this photograph is as much a captured subject as she is the co-artist of her own image.

What so upset that commenter is the thing that makes this image so powerful to many other people.

Of course it captures her posing. It's a picture of a Black woman controlling the picture. By assuming her stance, she makes herself available to a photographer who can make her appear to be enchanting, casting a spell on, the armed government.

After this moment, the officers will handcuff her. The photograph is the reverse of the actual power dynamics of the event—her arrest.

She and others were attempting to block a highway. Refusing, she was taken to jail for about a day, then released.

In their rush to overwhelm a slender, pretty, cooperative young woman in a flowing dress, the riot gear policemen look like cowards. They become the emblems of a cowardly government.

I use the word "cowardly" deliberately. It came up in In Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America, journalist Jill Leovy's book investigating the ongoing epidemic of Black men killing other Black men in South Central LA.

Leovy writes a shocking story. She documents the pattern of the American government cracking down hard on Black men for minor infractions while leaving them to kill each other without punishment in every major city, barely even trying to solve these murders, and therefore encouraging lawlessness and more violence and murder. The percentage of Black homicides that actually get solved is not much higher than it was in the horrifying Jim Crow South, astonishingly.

It is the greatest crime against Americans, she writes.

Leovy is a journalist, not an activist, and the Black Lives Matter movement never once came up during her recent interview on Fresh Air.

But Ghettoside is inherently a Black Lives Matter book. It's a book driven by data that documents Black lives, and deaths, not mattering. Sons disappearing while the most and best resources are redirected to drug possessions and the far rarer killings of people deemed important or noteworthy.

Leovy writes:

The failure of the law to stand up for Black people when they are hurt or killed by others has been masked by a whole universe of ruthless, relatively cheap and easy preventive strategies. Our fragmented and underfunded police forces have historically preoccupied themselves with control, prevention, and nuisance abatement, rather than responding to victims of violence. ...

Many critics today complain that the criminal justice system is heavy-handed and unfair to minorities. We hear a great deal about capital punishment, excessively punitive drug laws, supposed misuse of eyewitness evidence, troublingly high levels of black male incarceration, and so forth. So to assert that Black Americans suffer from too little application of the law, not too much, seems at odds with common perception. But the perceived harshness of American criminal justice and its fundamental weakness are in reality two sides of a coin, the former a kind of poor compensation for the latter. Like the schoolyard bully, our criminal justice system harasses people on small pretexts but is exposed as a coward before murder. it hauls masses of black men through its machinery but fails to protect them from bodily injury and death. it is at once oppressive and inadequate.

Leovy writes specifically about Black men, but the woman in Bachman's Baton Rouge photograph can easily be imagined among the "masses" of Black people who are hauled through an American criminal justice machinery focused on "ruthless, relatively cheap and easy preventive strategies," a system that "harasses people on small pretexts but is exposed as a coward before murder."

She protests a murder. While the killer is free, she's hauled in for a peaceful protest.

This same system cannot seem to reform itself even in order simply to bring better non-lethal tools to a police officer's job.

Let's talk about why it's important to note that this photograph is not only photojournalism, but also an artwork of staged photography.

It's because the photograph creates a fantasy that exists only in the photograph.

"She looks a superhero, and the over-dressed riot cops look like bumbling fools,” the Washington Post reported from Katrina Galore on Facebook.

"She looks like a queen greeting peasants,” Ali Bushby posted. “I love this photo so much. No violence, no anger, just the knowledge of moral superiority.”

Reportedly, the woman's name is Ieshia Evans. This was the 28-year-old's first protest, and to participate, she traveled all the way from New York, where she lives in fear of future police violence against her son, who's now 5. She is a nurse in real life. In the photograph, she appears almost to minister to the officers.

In the dreamscape of the photo, the Black woman stands against an army. Those numbers make her the ultimate minority: the individual against the state.

Some have said the photograph looks like a Beyoncé video. There is a point to that, but Beyoncé does wield actual power. She is a star. The photograph of an unknown woman is a piece of generative fiction that earns its importance by the opposition of the immediately adjacent facts. When the shutter closes, Evans is arrested, removed, and returned to powerlessness.

The picture is a fairytale, not a documentation.

Street protests are a special form of theater that can produce pictures that reverse or resist reality. I'd wager that the commenter who complained that the woman appeared to be posing has never attended a street protest. Anyone protesting is aware that they will be documented. They are aware of how what they are doing looks, and they construct an image accordingly.

If they are lucky, then a photographer will be able to comply, producing and disseminating an image that becomes a collective symbol, like Tank Man at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Evans knew she would be arrested, Bachman heard her say. She stepped forward and assumed the position knowing she might be photographed, in an attempt to create a record for herself other than a criminal one.

In other words, if you were to see this photograph as proof that the Black Lives Matter movement is no longer needed because Black women are now the equivalents of queens and superheroes in the social, economic, and political order of this nation, then you would be dangerously mistaken.

Evans got especially lucky because both the photographer and the officers are in exactly the right position to create the illusion.

In Bachman's photograph, she appears to do more than just resist, as an AP image taken at the same moment by another photographer depicts. Bachman's camera, by contrast, portrays her repelling the officers by some invisible force. The exact angles and timing of their posture completes the purpose that she began when she assumed the upright and firm position: to appear calm and proud, unmovable, in the face of injustice.

Evans also looks like Christ. The photographic composition, like a Baroque painting, is derived from a central triangle.

The triangle is formed by the legs and feet of the woman and the officers.

The top point of the triangle is where the far officer's legs form an upside-down V.

That V extends to two perfectly straight lines that intimately connect the three figures.

His right foot leads directly into the woman's dress. The line continues, running through to the dress's far right edge as the wind blows it.

The officer's other foot, his left, extends straight to the closer officer's right heel. Their legs rhyme, as in a synchronized dance.

The officers' uniformity and synchronicity makes them robotic, interchangeable, anonymous. Evans is the only individual in the photograph, which is, again, a reversal of reality. This time it's the reality that Black people suffer from being profiled as members of a group by the criminal justice system, rather than seen as individuals with individual stories.

Another fruitful lie contained in the picture is perhaps the question of height. I doubt that this woman is taller than the two officers who confront her. But because of the angle of the photographer's approach, she is the tallest figure in the picture. The entire line of riot gear officers in the background become small in relation to her. They are literally beneath her.

Her pose, as a still goddess in command rather than a woman about to be dominated and carted away (like so many females in mythology and art; see Titian and Goya for good examples), works so perfectly that it's almost a cliché. The officers are all action. She is equanimity itself. They look through obscuring masks, but she wears spectacles to see beyond them (at first I thought these were sunglasses, but these same glasses appear in other photographs of her online and appear to be corrective, clarifying).

Her profile is delicate and delineated, and her mouth is closed. She is not speaking or holding a picket sign: Her body is her language, and her dress is the dialect. Straps reveal her back, and slits reveal her legs. But the dress ultimately evokes the robes of a monk, or a prophet.

She first made me think of Christ in judgment. Especially her hands.

Evans's hands resemble the hands of El Greco's 16th-century Christ gripping the cross on his way to his own death. She holds nothing (discernible) in the photograph but you can picture El Greco's cross in the blank space between her arms.

Yet Evans wears no torment on her face. She isn't a martyr. Her face is from Buddha. Rather than a cross, she intends to hold her son's future in her hands.

In the process of folding her arms in front of her body, her right arm already rests on her body, but her left remains extended with her palm almost upright.

Going back to medieval Christian European art, Christ signaled his judgments of the damned and the saved using his hands. An upward palm (usually the right) signaled those headed heavenward; downward palm (usually the left) meant you were toast.

Evans appears to sit in judgment of the officers but with her hands in a mixed position.

Would she declare the officers lost or redeemable?

We wait to understand her judgment. She's suspending it for good reason. We wait to see whether our government will hear the call of Black Lives Matter. We wait to find out whether our society will understand it.