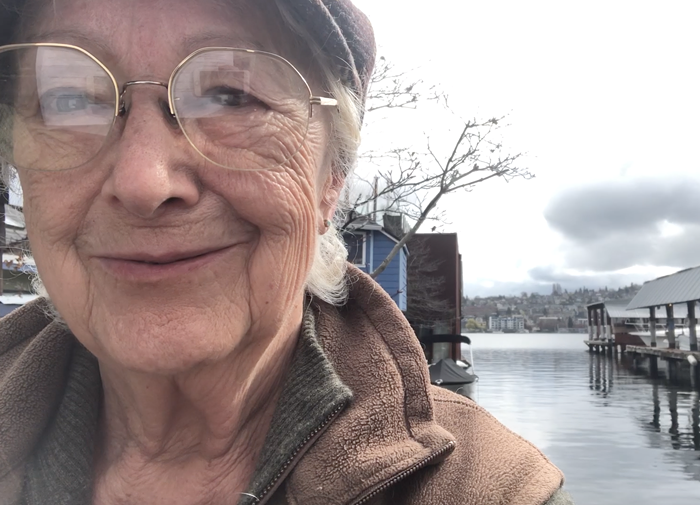

I met the Vancouver B.C.-based forest scientist Suzanne Simard on a sunny spring day in 2016. She was in town for an event at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation's LEED Platinum campus. We met at the McMenamins in Queen Anne to talk about her research, which concerned the nature and structure of tree sociality. I was informed of her work by her important contribution to Peter Wohlleben's popular The Hidden Life of Trees. And I had read this book because it presented a starting point for a project initiated five years before by a passage I encountered in Richard Dawkins' The Greatest Show on Earth.

This book was published in 2009. I read it in 2010 and came across the Forest of Friendship story/theory in its pages. Dawkins basically placed competition at the heart of evolution by dreaming up a community of trees (he is, by the way, a zoologist) that decided socialism (let's all stay the same height and save resources from competition) was the best way to make things work for all. But this noble plan was easily undone by one mutant tree that was greedy.

In Dawkin's own words:

Imagine the fate of a hypothetical forest - let's call it the Forest of Friendship - in which, by some mysterious concordat, all the trees have somehow managed to achieve the desirable aim of lowering the entire canopy to 10 feet. The canopy looks just like any other forest canopy except that it is only 10 feet high instead of 100 feet. From the point of view of a planned economy, the Forest of Friendship is more efficient as a forest than the tall forests with which we are familiar, because resources are not put into producing massive trunks that have no purpose apart from competing with other trees. But now, suppose one mutant tree were to spring up in the middle of the Forest of Friendship.This rogue tree grows marginally taller than the 'agreed' norm of 10 feet. Immediately, this mutant secures a competitive advantage.

Upon first reading this, something deep in me said: This has to be wrong. How in the world can something as rich and complex as nature operate in the same simple and desiccated way of the market as imagined by neoclassical economics? Indeed, that school's theory rarely even squared with diurnal economic experience. But here was Dawkins describing an ecosystem with the crass logic of Thatcherism.

After reading Wohlleben's short book in 2013, I began to read Simard's academic papers, such as "Reciprocal transfer of carbon isotopes between ectomycorrhizal Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii" (1997). They were packed by a technical language that I had to learn word by word.

A taste of that paper:

...Douglas fir grown in soils collected from beneath hardwoods (Lithocarpus densiflorus. Arbutus menziesii, Quercus chrysolepis) formed ectomycorrhizas predominantly with two types (Rhizopogon type and Cenococcum geophilum Fr.), whereas seedlings grown in soils collected > 4 m away from hardwoods formed less than half the number of EM tips with predominantly a single, unidentified brown type.

But once I grasped some of the terms and theories in Simard's field of science, a resolution of her deepest ideas emerged and sharpened. I began to see something like the forest in her research. And it, to my growing surprise, was as strange as watching a whole UFO descend from the clouds on a moon-bright night. But Simard's forest life made clear was aliens don't need to come from outer space. They are already here, already rising around us, already in the ground beneath our feet.

"I experienced the forest as an entwined place, where all the trees are interdependent....a cathedral that was one, with all of its disciples & pews."

Brilliant interview w/ Suzanne Simard, whose pioneering research helped disclose the "Wood-Wide Web".https://t.co/AR1wNXluVE

— Robert Macfarlane (@RobGMacfarlane) May 3, 2021

Without a thought, I ordered a glass of the house white wine from the McMenamins server operating our table in a booth by a window with a view of Roy Street; with a second thought, Simard decided to order a beer. She was, clearly, not the type to let someone drink alone.

I asked her lots of questions. She answered all of them with a calm that almost unnerved me because it was not a calm I was familiar with. It had the feel of being in a zone that was not entirely human. Something else was mixed with it, mixed with the way she expressed herself and processed her thoughts. At the end of my glass of wine, and as I ordered another (she had downed a third of her beer), I reached the conclusion that Simard spoke like someone who had been raised by trees, in the way Tarzan was raised by gorillas..

Our conversation lasted a little under two hours. She had to return to the event at the Foundation by 4 pm. I thanked her for her time and, as I waited for an Uber on a spot right in front of the window of the booth we had just shared, she walked dreamily down a sidewalk lined by the most pathetic looking trees.

On March 3, 2021, I learned that Simard had a book coming out. My plan, at first, was to read it upon its release on May 4. But when I further learned that Simard was the reader of her memoir, I decided to replace the words that would have appeared in my head with the scientist's own words. I wanted to hear that strange, arboreal calmness again. Was it real? Or did I just make it up during our conversion on the spring afternoon?

Long before the short introduction of her book was completed, I knew from her voice that it was real. Simard is part tree. I didn't make stuff up during our 2016 McMenamin moment. You can hear it as Simard reads about how she ate mud as a rude Pacific Northwest girl, and how she was raised by a lumber family, and how she worked for a corporate lumber company, studied forests in college, and clung to a tree when a bear wanted to kill her. The science of her work on what calls mother trees and the wood-wide web is clearly explained in the book, which, like Jonathan Raban's Passage to Juneau, is a masterpiece of Pacific Northwest literature. The fungal networks below the forest floor are ancient and complex.

On my floor mattress, my back straight against the wall, I stared at my three prehistoric-looking mushrooms. They were helpers to plants, mycorrhizal fungi. That was what my mushroom book was telling me. I read a little further and found another startling passage. The mycorrhizal symbiosis was credited with the migration of ancient plants from the ocean to land about 450 to 700 million years ago. Colonization of plants with fungi enabled them to acquire sufficient nutrients from the barren, inhospitable rock to gain a toehold and survive on land. These authors were suggesting that cooperation was essential to evolution. ...[W]hy did foresters place so much emphasis on competition?

This is Simard at around age 23. She is in the middle of a deep forest with a friend, a bottle of wine, tuna-rice casserole, and pieces of a chocolate cake. The trees are beginning to speak to her. What she has felt all her life is coming true. The blood in her body is fused with the Douglas fir and other species of the forest. Her way forward is as clear to her as the light leaves use to produce the sugars of life.

Elliott Bay Books hosts Suzanne Simard Monday at 6 PM virtually.