The Books of Love

Charlie’s Queer Books Is a Welcoming Space for Seattle’s LGBTQ+ Lit Nerds

The Future of HIV Treatment Is Injectable

Promising Drugs Could Expand Treatment–If We Get Out of Our Own Way

What’s Next for Denny Blaine?

Maybe New Rules, but Certainly Fewer Thorns

Getting High with Seattle Cheer

A Very Queer Play Date

Dave Upthegrove Wants to Save the Trees

...And Become Washington State’s First Gay Executive While He’s at It

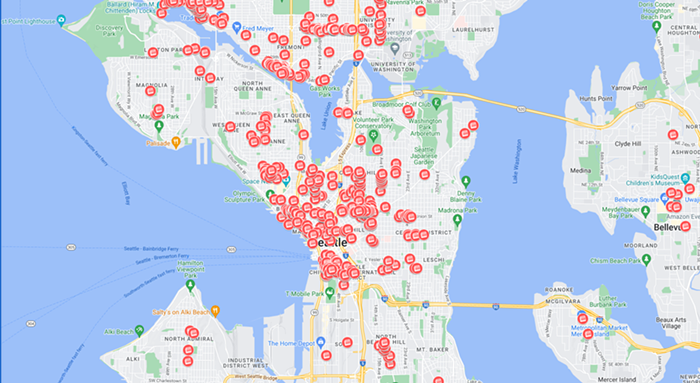

Queer Issue 2024 Pickup Locations

Looking for a Copy of This Year’s Queer Issue? You Can Find One at the Following Locations.

Can Seattle Drag Afford to Stay Weird?

Rising Costs, and Fewer Beginner-Friendly Venues, Are Sanitizing Seattle’s Drag Scene

50 Years of Queers

Gay Betrayals! Rich Prudes! Queer Futures! And an Absolutely Stuffed Pride Calendar!

The Gays Who Slayed and the Gays Who Betrayed

Not Every Queer Politician Is an “Ally”

Letters to Our Younger Trans Selves

What We Wish We Knew

The Reality Behind the Story I Told The Stranger

I Said I Was Detrans, but Really I Was Struggling

Out of This World

Forming the SassyBlack Universe

The Futures of Seattle’s Gayborhood

An Architect, an Urban Planner, a Documentarian, an Academic, and a Business Owner Imagine What Capitol Hill Will Look Like in 50 Years

The Biggest Pride Month 2024 Events in Seattle

Festivals, Parties, and More All Throughout June

After speaking on behalf of south King County residents for the better part of 22 years as a State Representative and as a King County Council Member, Dave Upthegrove now wants to speak on behalf of the trees as Washington’s next Public Lands Commissioner.

The position would put him in charge of the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), which oversees the state’s seven million acres of “forest, range, commercial, agricultural, conservation, and aquatic lands,” according to its website. Despite high concentrations of lumberjacks and firefighters around the agency, if elected he’d somehow become the first gay person to run it. In doing so, he’d also become our first openly gay statewide officeholder. That’s progress, baby!

That ceiling, however, will be a tough one for him to crack. Though at this point in the culture wars he fears his King County roots will hurt him at the ballot box more than his status as an LGBTQ leader, Upthegrove faces stiff competition in the upcoming August primary, including a timber industry willing to pay to put a chainsaw in office. But as a career environmental and queer activist, Upthegrove is no stranger to long, hard roads.

You Can’t Run for Office

Upthegrove came out publicly in 2001, the year he first ran for office. With a gesture and a plural pronoun, he slipped the admission into a speech he delivered as part of an appointment process to represent the 33rd Legislative District in Olympia. “Those of us who are gay and lesbian,” he said, pointing to himself, pretending as if everyone knew. And that was that.

When his mentor learned the news, he said, “I love you, Dave, but it’s too bad because now you can’t run for office.”

At that time, the thought of an out, gay legislator deep in the heart of south King County was unheard of, Upthegrove said in a phone interview with The Stranger. Nevertheless, he won the appointment and became the state’s first out LGBTQ legislator to hold office outside of Seattle.

Though he helped pass marriage equality and anti-discrimination laws, when reflecting on his proudest accomplishments for the community, he feels his visibility as a gay person in the world represents some of his “most impactful work.”

He said he always outs himself in front of church crowds and groups of young people, even if he’s not in the room to speak on LGBTQ issues, because he knows there will be one or two closeted kids sitting in the audience. As a closeted kid who grew up in a morass of anti-LGBTQ hate, he knows firsthand how empowering such role models can be.

As the state’s first openly gay executive, he’d hope to emulate Department of Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg’s style as a policy wonk who uses his bully pulpit to fight bigotry. “My focus is going to be on trees and geoducks and agriculture, but I’ll be out and visible to try to break down stereotypes, and I’ll speak up when there’s injustice,” he said.

That passion for justice drove his early career, he said, and it still drives him today. And it’s that same sense of justice that drives his thinking on the environment.

Portrait of the Politician as a Young Environmentalist

Though he became an LGBTQ leader when he entered office, the environmental movement is what led him into politics in the first place. His love affair with the outdoors started at a young age. He said he spent his summers teaching environmental science to kids out on the Hood Canal, and he spent a couple summers leading week-long tracks through the North Cascades.

The political bug bit him at the University of Colorado, where he became an environmental activist and earned a degree in environmental science before later picking up a graduate certificate in energy policy at the University of Idaho.

He couldn’t find a job right out of college, so he worked for the forest service before landing a gig as a committee clerk in Olympia. In that role, he fell in love with the Legislature, and he ended up bopping around as an aide with enviro-focused politicians for years until deciding to run for office himself.

In Olympia, he worked with Governor Christine Gregoire to create the Puget Sound Partnership, a state agency designed to protect and restore the Sound. He later chaired the House Environment Committee for years, helping to guide through the House legislation that shut down the state’s last polluting coal plant.

In his off hours, over beers he helped organize a blue-green alliance, building a coalition that ended up wielding some factional power in Olympia on behalf of labor and environmental activists. He also helped pass and fund legislation requiring the state to test soils around schools, day cares, and playgrounds for high levels of contaminated dirt.

Saving Our Older Forests

If the voters will it, he vows to take the passion for environmental justice that he fostered in the Legislature with him into the Department of Natural Resources, where he’ll essentially serve as the state’s landlord.

On “day one” of his tenure he’d sign an order to save “mature legacy forests” from the buzzsaw. Those forests aren’t technically old growth but they’re close. Unlike a tree farm, Upthegrove said, they “naturally regenerate, they’re diverse, and they support a lot of biodiversity.” The trees aren’t just pleasant to be around, either. Though they only make up 3% of our state-owned timberlands, they have “an outsized impact on carbon storage,” he said.

To make up for any loss in state revenues and jobs, Upthegrove plans to use existing state funding streams to acquire replacement timberlands from private owners, on whose land 70% of the state’s forestry takes place.

Detractors worry such a move would cut into school funding, since the state directs to K-12 construction the proceeds of timber sales on some public land, but Upthegrove argues that all of the money generated from those sorts of sales accounts for about “1.5% of the state’s share of new school construction.”

“So obviously we need to fully fund our schools, but the pathway is not through DNR, and [Superintendent of Public Education] Chris Reykdal has gone on the record saying he doesn’t even need it,” he added.

He also wants the agency to take into account carbon storage and sequestration goals “in a meaningful way” as part of the new sustainable harvest calculation the agency will soon need to adopt. “When we engage in a timber sale right now, there’s no carbon accounting,” he said.

When it comes to addressing the wildfires that choke summer skies on a regular basis, Upthegrove endeavors to more or less carry on and attempt to improve upon the legacy of outgoing Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz.

Whereas Franz focused on upgrading the state’s response to fires and spearheading the creation of the Wildfire Response, Forest Restoration, and Community Resilience account, he wants to focus on prevention and on finding a stable source of funding for that account.

Upthegrove isn’t the only candidate in this race with ideas about trees, but he is the only one with endorsements from Washington Conservation Action and the Sierra Club, two heavyweights in the enviro fundraising and organizing worlds. So far, he’s also raised the most money, with north of $370,000.

Former Republican Congresswoman Jamie Herrera Beutler trails closely behind him. Other Democrats in the race include state Sen. Kevin Van De Wege and Makah Indian Tribal Council Member / member of the DNR executive team Patrick DePoe, who Lands Commissioner Franz endorsed. Big and smaller timber have thrown money at both Herrera Beutler and Van De Wege. Lots of DePoe’s money comes from the tribes.

With a couple other Democratic politicians in the race, the primary election results in this contest are far from certain. He’ll need all the help that he can get from the gays and the greens. ν