The Books of Love

Charlie’s Queer Books Is a Welcoming Space for Seattle’s LGBTQ+ Lit Nerds

The Future of HIV Treatment Is Injectable

Promising Drugs Could Expand Treatment–If We Get Out of Our Own Way

What’s Next for Denny Blaine?

Maybe New Rules, but Certainly Fewer Thorns

Getting High with Seattle Cheer

A Very Queer Play Date

Dave Upthegrove Wants to Save the Trees

...And Become Washington State’s First Gay Executive While He’s at It

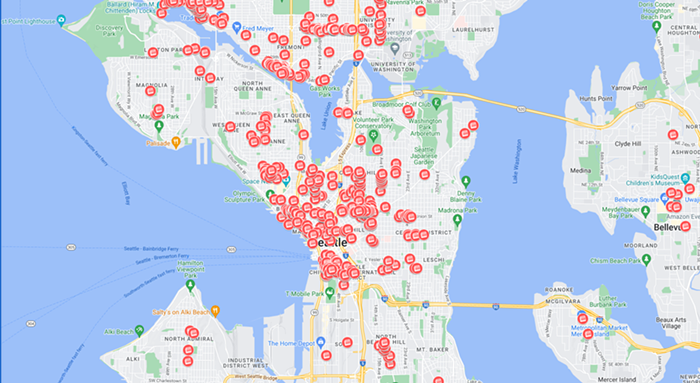

Queer Issue 2024 Pickup Locations

Looking for a Copy of This Year’s Queer Issue? You Can Find One at the Following Locations.

Can Seattle Drag Afford to Stay Weird?

Rising Costs, and Fewer Beginner-Friendly Venues, Are Sanitizing Seattle’s Drag Scene

50 Years of Queers

Gay Betrayals! Rich Prudes! Queer Futures! And an Absolutely Stuffed Pride Calendar!

The Gays Who Slayed and the Gays Who Betrayed

Not Every Queer Politician Is an “Ally”

Letters to Our Younger Trans Selves

What We Wish We Knew

The Reality Behind the Story I Told The Stranger

I Said I Was Detrans, but Really I Was Struggling

Out of This World

Forming the SassyBlack Universe

The Futures of Seattle’s Gayborhood

An Architect, an Urban Planner, a Documentarian, an Academic, and a Business Owner Imagine What Capitol Hill Will Look Like in 50 Years

The Biggest Pride Month 2024 Events in Seattle

Festivals, Parties, and More All Throughout June

Sometimes on a Sunday night you find yourself holding a woman up by the soles of her feet.

I gripped Stevie Escobedo, 33, by her white sneaker. Beside me, Anthony Alston, 53, cradled her other shoe. He breathed the counts of the routine we had just rehearsed in pantomime. I couldn’t remember the counts, so I mimicked Alston, keeping one eye on him and the other on Escobedo, who, from my vantage point, was all leg. Her torso and head poked out from above her knee. I’d never seen a person from this perspective. “That’s fun,” I thought. Similarly, no one had ever trusted me with their life like this. And, should they have?

“Six, seven, eight,” Alston called. We raised Escobedo up, then down. My fingers turned white from squeezing her shoe so hard. Any wobble and she’d topple. Somehow, she dismounted in one piece.

Le Carr, 32, who had been spotting from the back as an aptly named “back spot,” turned to me. “Are you ready to get up there?”

I shrugged. Why not?

For my latest exploration into Seattle subcultures, I hoisted myself onto the shoulders of Cheer Seattle’s “queerleaders” to figure out what this majority-LGBTQIA nonprofit was all about and to determine the origin of the pep in its step.

In doing so, I met a group of people changing a historically gendered sport by stripping away its more restrictive rules and stereotypes. What’s left behind is all the elements of cheerleading glossed over in pop-culture: the positivity, the enthusiasm, the teamwork, the trust.

Formed in 2014, Cheer Seattle is part of the 14-team nationwide Pride Cheerleading Association. The group aims to allow LGBTQ+ members and their allies to perform while raising money for good causes and awareness about the queer community.

Cheer Seattle hosts three teams: a stunt team (Sapphire), a dance team (Emerald), and a production team (Diamond), so anyone who’s interested in cheer has a place. They cheer at sporting events, they volunteer at fundraisers and races, and they perform at Pride. This year, Cheer Seattle’s raised funds will go toward The Lavender Rights Project, a Washington-based group focused on Black trans women.

“It [feels] like using my powers for good,” Alston said. “Going to Pride events year after year is one thing, but being in the parade and raising money for a local charity is really inspiring and motivating.”

Alston was one of three people who started Cheer Seattle 10 years ago. The group’s origin, however, starts in San Francisco.

Alston joined Cheer San Francisco, the first of the PCA teams, back in 2001. A gay Seattle transplant adrift in a post-dot-com-bust and post-9/11-world, he needed community. As a lifelong self-proclaimed band geek marching on football fields next to cheer squads, he said he’d always harbored a desire to take up a pair of pom-poms of his own.

“I always saw the cheerleaders, and I was like, ‘One day, that would be cool,’” he said. “But I thought I was too old.”

When Cheer San Francisco started recruiting back spots, he joined.

“Wearing that uniform was awesome,” he said. ‘I’m getting chills just telling you about it because it brings back a flood of memories.”

He led the San Francisco Pride parade for six years, driving his truck equipped with blaring freight train horns and leading 300 cheerleaders from San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Sacramento, all doing stunts along the way.

“Looking down Market Street and everyone is waiting for us to start the parade, the anticipation, the energy, the excitement, and then you’d see basket tosses! Basket tosses! Basket tosses!” He said, gesturing with his hands, his fingernails painted blue and green. “When you’re performing, you’re connecting with your community, you’re connecting with the crowds, you’re hyping them up, you’re giving them something.”

As he gets older, performing takes more of a toll on his body—“I’ve sacrificed both my biceps to cheer,” he said, yet he still can’t give it up.

“There’s no other high that satisfies me that much,” he said.

When he moved back to Seattle, he knew he needed to start a PCA team. So he did. Now, while performing still gives him that high, he also derives satisfaction from watching people grow because of this thing he started.

“What they were getting out of the experience—people who had never cheered before, who wanted to fly, who wanted to base, who wanted to dance and perform—they got those experiences through Cheer Seattle,” he said. “I’m glad to facilitate that. It’s like a proud papa moment.”

A Gayer High School Do-Over

Escobedo recently moved to Seattle from Colorado after realizing she was queer. Determined to explore that, she made the difficult choice to part ways with her then-husband, who is still her best friend, and branch out on her own.

“I was trying to figure out who I am as an adult, as a human,” she said. She found Cheer Seattle last October.

Escobedo cheered in high school, but she hadn’t picked up any pom-poms since. Picking them up again as an adult felt like a high school do-over–except, this time way gayer.

“I definitely feel like I’ve been going through my queer adolescence this whole time,” she said. “I’m reliving high school in such a different space.”

As a late-blooming queer person, she says things like the act of coming into your sexuality during the prime of adulthood can often be difficult and lonely.

“It’s rough just as it was the first time, as it was in high school; the pains, the awkwardness, the discomfort … Even coming onto a cheerleading team and being 33—that’s probably not the most comfortable thing, but the more you can live in that discomfort, the more you’re going to experience life,” she said.

Rediscovering a sport she loved alongside a team full of fellow LGBTQ+ people helped her grow, and now she wants to help Cheer Seattle change and grow, too.

“Everything has been passed down in cheerleading,” she said, speaking of the traditions and the status quo of the sport. “But we’re the queer community, we’re the queer community in Seattle,” she snapped her fingers. “Let’s cunt it up!”

Binary Bustin’

Since the pandemic, Cheer Seattle has gone through some big changes of its own. One big change has been around fliers.

Spencer Watson, 30, came out as gay in Boise, Idaho when he was 12. Right around that time, he joined his first cheerleading team. He was the only boy, but he didn’t care. He fell in love with cheerleading and it changed his life, both personally and geographically.

He left Idaho after senior year to join an all-star cheer team in Kent, Washington.

“The driver [for my move] was Seattle; like, I’m gonna bloom as a big ol’ gay boy here, not in Idaho,” he said.

Throughout his 18 years of performing cheer and his 15 years of coaching it, Watson, now a coach at Cheer Seattle, never flew, the position in cheerleading where you’re tossed in the air like a little sack of potatoes with pointed toes. Despite teaching the skill, Watson never tried it. He wasn’t allowed.

Traditional cheerleading harbors a stereotype where “boys don’t fly,” only women fly. “That’s their role,” Watson said. “It’s this binary gender role that I’m not here for.”

When he first started coaching at Cheer Seattle four years ago, he tried to change the flier rules. Even in a progressive, boundary-pushing organization, it took years for the change to catch on universally versus on a case-by-case basis. In the last four years, that’s changed.

“It’s been such an inspiration for all the other members who had wanted to fly but didn’t feel they had not only the gender to fly but the body type to fly,” Watson said. “There are so many other factors that play a role in flying than weight, or, fuck, your gender.”

Tony Thompson, 37, never cheered in his life before joining Cheer Seattle. Now, as a performer, he wants to do it all.

“I’m mainly a backspot, I help lift the flier into the air,” Thompson said. “But, I’m trying to be a triple threat. I also want to be a base, and I also want to fly next season. The fliers get most of the face time, and having a queer male flier out there would be really good. I’m trying to bring more representation into the air.”

He continued: “I’m not trying to throw a Showgirls moment, but I will do a Showgirls moment.”

All body types and all genders can fly at Cheer Seattle. Thompson says that Cheer Seattle is the “most queer-diverse” of the cheerleading teams.

“We push that envelope,” he said.

For the Enbys

Speaking of breaking cheerleading norms, Cheer Seattle recently started offering gender neutral uniform options.

“We try to get away from the binary,” Thompson said. “We can wear whatever we want to wear.” Maybe that’s a skirt, maybe that’s leggings.

It’s one way of dismantling rules around a sport which, for decades, was been built on norms around femininity.

Carr, who I originally met when they taught me how to powerlift, grew up cheerleading at a highly competitive level before an injury ended their cheer career.

“I obviously really value the competition and the sportiness of it, but I also really struggled with a lot of the feelings of belonging, at least when I did it back in Georgia,” Carr said

Carr came out as nonbinary in the years since they last did a back handspring.

Last summer, they found Cheer Seattle after drunkenly googling “queer cheerleading” at Queer/Bar. They sent in an application at 2 am and have been with the squad ever since.

Carr described Cheer Seattle as “a way of cheerleading that has all the positives.”

The team serves as a foil to the stereotypical perception of cheerleading; you know, the mean girls, the cliques, the drama.

“It is absolutely not intimidating and it is not exclusive,” Carr said. “It doesn’t matter if you’ve had 12-plus years of experience or never cheered before in your life.”

They told me this, and then–true to their word–they coaxed me to fly.

On Top of the Pyramid

I gripped Carr’s and Alton’s shoulders. With my arms straight, I leaned all my weight onto their bodies and pulled myself into a ball, my knees level with their ears.

All I could focus on was the thought of causing them pain.

“Am I hurting you?” I asked.

They both told me no, I was fine. Beneath me, their bodies braced. They felt solid. This was why they were called bases.

“Three and four and…” someone–maybe everyone–counted, and I swung my feet into each of their hands. They held me aloft. “What the hell, what the hell,” I thought. How was I going to stand up?

A different person called: “Keep your arms by your sides and straighten your arms!” As someone most comfortable within the confines of rules and instructions, I obeyed happily.

Then, even though I knew it was coming, I completely forgot the part where Carr and Alston would heft me up while I stood on their hands. Unexpectedly, they propelled me upward so I was towering above the School of Acrobatics and New Circus Arts’ practice area. My stomach dropped, my heart fluttered, everyone looked up at me while I looked down on them. This was a new perspective, too. I stretched my arms up, keeping my body as straight and grounded as I could.

I stretched my arms out wide, my fists curled loosely like cinnamon rolls, like a cheerleader.

Around me, the rest of the squad practiced legitimate basket tosses, throwing their fliers into the air and catching them.

Despite the new heights, I never worried about falling. The team below me, most of whom I’d just met, would catch me–I was sure of that. The trust required for this sport seemed greater than the athleticism, I thought. And yet, depending on these people felt like second nature.

Gently, the bases lowered me down and eased me into a dismount.

As I stood on the ground, my body vibrated. I simultaneously felt like I’d just walked off a rollercoaster and like I’d just chugged a coffee on an empty stomach. My head swam, my pulse raced. Everyone around me patted me on the back, showering me with compliments. I could see how cheerleading could become an addiction.

“We’ll teach you tumbling next,” Carr said.

View this post on Instagram